The Players in the Protection of the EU’s Financial Interests European Cooperation between Authorities Conducting Administrative Investigations and those Conducting Criminal Investigations

Abstract

Cooperation between authorities conducting administrative investigations and those conducting criminal investigations at both the EU and Member State levels is essential to ensure a high level of protection in view of the EU's financial interests. However, the legal framework governing the role and competences of individual authorities at the EU level seems much clearer than the corresponding national legal frameworks of the Member States. Indeed, at the Member State level, the legal frameworks for conducting investigations, whether administrative or criminal, significantly differ from Member State to Member State. Likewise, there is no clear legal framework at the EU level that defines and sets standards regarding the mandatory control mechanisms that must be established at the level of the entire system for the protection of the EU’s financial interests in the Member States. This also applies in relation to the players that need to be involved in the protection of the EU's financial interests. The article tackles the issue of the necessity to harmonise both criminal and administrative legislation at the level of Member States as well as the need for a clear definition of which players should be involved in the protection of the EU budget.

I. Introductory Remarks

Today, when the EU Member States (and the whole world) are faced with the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters, and war conflicts, an unprecedented amount of money is provided to overcome these crises. This creates opportunities to commit serious irregularities, frauds and corruption. It is therefore, more than ever before, important to clearly define sustainable and efficient control framework and the key players involved in the protection of the EU’s financial interests

On 17 December 2020, following the European Parliament’s consent, the Council adopted the Regulation laying down the EU’s multiannual financial framework (MFF) for 2021-2027.1 The Regulation provides for a long-term EU budget of €1.074 trillion (in 2018 prices) for the 27 EU Member States.2 Together with the NextGenerationEU recovery instrument of €750 billion (in 2018 prices),3 the EU will provide an unprecedented €1.8 trillion of funding over the coming years to support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and implementation of the EU’s long-term priorities across different policy areas. For the European Commission, a major priority is to protect the taxpayers’ money and to ensure that every Euro from the EU budget is spent in line with the rules and generates added value. In this sense, the Commission works closely with the Member States and other respective EU institutions towards these objectives.

Against this background, the present article will illustrate which key players (both those that conduct administrative investigations and those that conduct criminal investigations) are involved in the protection of the EU’s financial interests and which control mechanisms are available to protect them, both at the EU and national levels. By way of a preliminary remark, we should bear in mind a number of important aspects: First, the players involved in the protection of the EU’s financial interests handle both EU revenue and expenditure; the protection of the EU’s financial interests is equally ensured within the legal framework for administrative proceedings and that for criminal proceedings. Second, the legal frameworks for conducting investigations, whether administrative or criminal, are significantly different from Member State to Member State, which often affects the efficiency of investigations and cooperation between the states. Third, the legal framework governing the role and competences of individual authorities at the EU level, which prescribes their mandate, the manner of proceedings, and obligations for mutual cooperation, communication, and the exchange of information seems much clearer than the corresponding national legal frameworks of the Member States. This is especially true when it comes to the recognition and understanding of the functioning of the legal framework for administrative proceedings.

II. Setting the Scene I: Cooperation between Authorities Conducting Administrative Investigations and those Conducting Criminal Investigations at the EU Level

At the EU level, several EU bodies are involved in the protection of the EU’s financial interests. This includes the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), the EU Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation (Eurojust), the EU Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol), the European Court of Auditors (ECA), the European Court of Justice (CJEU), and the recently created European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO). Many experts believed that the EPPO was the missing link in strengthening the fight against fraud and corruption in the EU, especially due to OLAF’s limited powers. At the heart of the protection of the EU’s financial interests are obviously OLAF and the EPPO. However, OLAF conducts administrative investigations at the EU level, while the EPPO conducts criminal investigations and prosecutes criminal offences falling under its competence before the national courts. It is important to emphasise that OLAF has maintained its operational independence, even in relation to the EPPO, and its field of operation is larger than that of the EPPO, because its competence extends to the entire EU, whereas the EPPO has only competence within the participating Member States.

The EPPO’s and OLAF’s fields of operation are nonetheless closely linked. The common aim of both bodies is to increase fraud detection at the EU level, to avoid duplication of work, to protect the integrity and efficiency of criminal investigations, and to maximise the recovery of damages to the EU budget. In addition, both bodies are combining their investigative and other capacities to improve the protection of the EU’s financial interests. In this context, Art. 12e(3) of the amended OLAF Regulation4 is worthy of mention: it obliges OLAF to observe the applicable procedural safeguards of the EPPO Regulation5 if OLAF performs supporting measures requested by the EPPO. This is an important step forward in ensuring the admissibility of evidence as well as fundamental rights and procedural guarantees.

Consequently, the working arrangement between OLAF and the EPPO6 is of utmost importance for their relationship. It specifically sets out how the two bodies will cooperate, exchange information, report to each other, transfer potential cases, and support each other in their investigations. It also covers the way in which OLAF will conduct complementary investigations, if needed. Last but not least, it ensures that the two bodies regularly share information on fraud trends, carry out joint training exercises, and carry out staff exchange programmes.

Currently, it seems that the cooperation between OLAF and the EPPO is proceeding smoothly and that all obstacles, if any, are being resolved without major problems. It is evident from OLAF’s activity report for 2021 that OLAF’s investigators provided support to the EPPO by serving as expert witnesses in complex cases, and they provided forensic analysis of and substantial documentation on relevant EU projects and programmes.7

In addition, in its first annual report,8 the EPPO gives an account of the initial seven months of its operational activity; it contains information on cooperation with other institutions, bodies, offices and agencies of the EU, including OLAF. Accordingly, the EPPO received and processed 2832 reports related to various cases of economic fraud in the EU and opened 576 investigations, 515 of which were still active on the last day of 2021. In these first seven months of the EPPO’s operational activity, OLAF contributed considerably to the opening of criminal investigations conducted by the EPPO: some 85 criminal investigations were opened by the EPPO based on OLAF’s investigative reporting.

In Croatia, the EPPO is currently conducting eight active investigations in which the estimated damage is €30.6 million and €270,000 have been seized so far. During complementary investigations and in close cooperation with the EPPO, OLAF conducted two on-the-spot checks combined with digital forensic operations in Croatia. In November 2021, four suspects were arrested at the request of the EPPO.

III. Setting the Scene II: Cooperation between Authorities Conducting Administrative Investigations and those Conducting Criminal Investigations at the Level of the EU Member States

When it comes to the players involved in the protection of the EU’s financial interests at the level of the Member States, there are some inconsistencies compared to the players at the EU level.

With regard to criminal investigations, the first observation is that the question of which authorities are recognised as conducting criminal investigations at the level of the Member States is clear. The authorities competent for conducting criminal investigations and prosecutions of offences against the EU’s financial interests are (most often) police forces, and – clearly identified – judicial bodies, or sometimes also specialised (anti-fraud) bodies.

Questions arise by virtue of significant differences in national criminal legal frameworks. Their application varies considerably among the criminal investigation and prosecution authorities of the Member States. This also includes the unequal compliance of the national criminal legislations of the Member States with the PIF Directive.9 In this sense, significant efforts should be made to harmonise criminal legislation as much as possible at the level of the Member States, such that criminal investigation and prosecution authorities in all EU Member States have the same mandate and legal basis for the performance of their duties concerning the protection of the EU’s financial interests.

By harmonising the description of criminal offenses against the EU’s financial interests and the way of their prosecution and penalisation at the level of the Member States, it would be possible to largely remove the existing obstacles for mutual cooperation, communication, and the exchange of information between competent authorities in the Member States, including obstacles and inequalities that exist in relation to their cooperation with the EPPO and other relevant institutions at the EU level in the field of criminal investigations/prosecutions against and sanctions for perpetrators of EU fraud. Such strengthened harmonisation efforts would contribute to individual acts being treated in the same way and preclude the fact that acts pertaining to the same factual situation represent a criminal offense in one Member State, while they are not even considered a misdemeanour in another. Likewise, it is very important to understand that the EPPO applies and operates within the framework of the national criminal legislation of the participating Member States. Any differences in national criminal legislation at the level of the Member States is also reflected in the different approach of the EPPO to cases containing the same facts, depending on how the protection of the EU’s financial interests is regulated by the criminal legislation in an individual Member State.

With regard to administrative investigations, the landscape of authorities at the level of the Member States that are competent for or participate in the protection of the EU’s financial interests is much sketchier than in the criminal law field. So-called country profiles, which would provide knowledge in this sense, have not yet been prepared, as far as can be seen. It is therefore very difficult at the moment to discern which authority/-ies in each Member State is/are involved in the protection of the budget and which legal framework for their cooperation, communication, and exchange of information, particularly with the authorities responsible for criminal investigations and prosecutions, applies. What can be stated at this stage is that the national systems protecting the EU’s financial interests by means of administrative law significantly differ from Member State to Member State. Next to the complexity of the matter and the process itself, the sufficiency, quality, and effectiveness of the different existing systems have never been compared.10

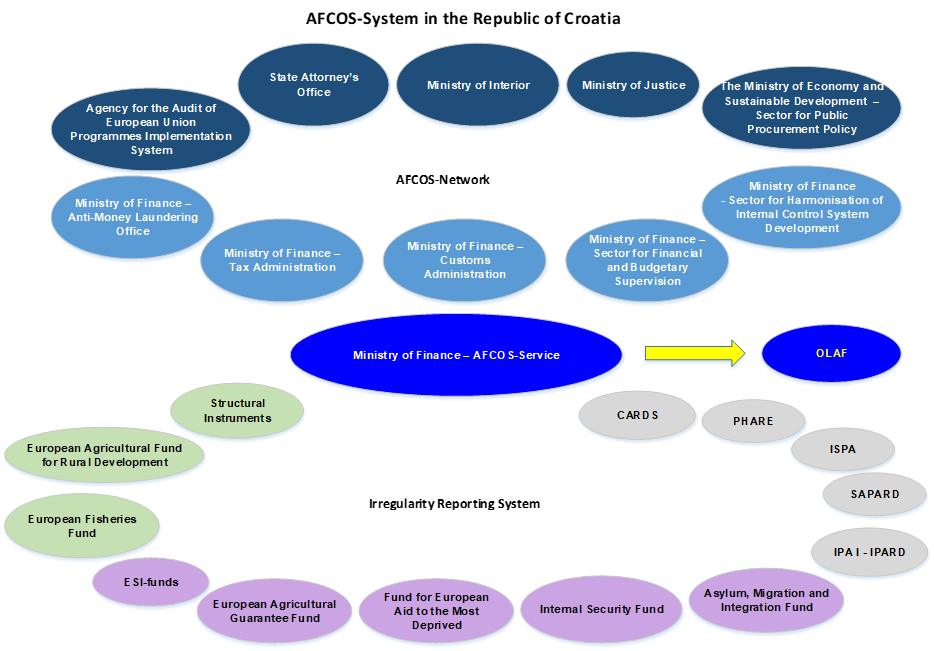

The complexity of the system of authorities involved in the protection of the EU’s financial interests can be demonstrated with the following chart giving an overview of the situation in Croatia.

In this context, a closer look at the audit system merits closer inspection: National and European audit authorities carry out regular audits on the management and control system of the EU funds (so-called system audits), but they do not perform audits on the entire system for the protection of the EU’s financial interests. In addition to the management and control system of the EU funds, it should be considered whether audits need also include the authorities that perform administrative and criminal investigations (i.e. those authorities that are outside the management and control system of the EU funds), including the anti-fraud coordination services (AFCOS),11 in order to check whether these authorities perform duties within their competence or not. If an audit on the part of the authorities participating in the protection of the EU financial interests, which are outside the management and control system of the EU funds, is not carried out, how we will gain insight into the effectiveness of the cooperation between the authorities that conduct administrative investigations and those that conduct criminal investigations?

Until then, our conclusions about the effectiveness of cooperation between authorities that conduct administrative investigations and those that conduct criminal investigations, and about the functioning of the entire system for the protection of the EU’s financial interests in the individual Member States, are based primarily only on the number of successfully resolved cases regarding established irregularities and fraud and the amount of recovered money. As a result, there is currently no valid, uniform basis by which to discern whether there is sufficient staffing, quality, efficiency, and effectiveness in terms of the role and work of other players involved in the protection of EU’s financial interests, apart from the authorities that are responsible for the management and control system of the EU funds (i.e. authorities that conduct administrative and criminal investigations, including AFCOS Service).

In order to ensure a high level of protection of the EU budget, we should strive for a clearer overview of which “administrative players” are involved in the protection of the EU’s financial interests at the level of the Member States. What is their status? What is and what should their role be in the protection system? What would be the best approach for the audit of such a system, so that it is not limited only to the authorities responsible for the management and control system of the EU funds?).

IV. Challenges and Open Issues

In the previous section, we have already identified that the significant differences in the national legal frameworks conducting investigations is a major challenge, which primarily affects the efficiency of investigations and cooperation between the EU Member States.

Another interesting challenge is posed by the fact that there is no common understanding of the meaning of several terms in relation to investigations, such as: “conducting on-the-spot checks”, “conducting administrative control”, and “conducting administrative investigation”. As also mentioned in the previous section, there is no common understanding of which (administrative) authorities are responsible for performing which type of control activities. Even the term “administrative body” is interpreted in different ways in the various Member States. Terminology has also not been harmonised at the EU level. It is unclear whether the term “administrative body” only covers authorities within the management and control system of the EU funds or also authorities that conduct administrative investigations/inspections that are outside of the management and control system of EU funds (e.g. tax, customs, and budget supervisory authorities).

To put it differently, on the one hand, the concept of on-the-spot controls carried out by the authorities operating within the management and control system of EU funds (i.e. managing authorities, paying agencies, and certifying bodies, cf. supra) is often associated with the exercise of administrative control. On the other hand, administrative control can also be perceived as the exercise of so-called ex ante control (in cases preceding payment), which can be carried out both by the authorities responsible for the management and control of EU funds and by individual administrative authority/-ies that is/are outside of the management and control system of the EU funds (cf. supra). Another layer in this context pertains to the fact that administrative authorities conducting inspections/investigations are by nature not designed to carry out ex ante but only ex post controls (in cases following payment). Consequently, the question arises as to which administrative authority at the national level of the Member States (outside of the management and control system of the EU funds) should be assigned ex ante controls or whether an authority should have the mandate to perform both ex ante and ex post controls like OLAF, which served as a model for instance for the Romanian Fight Against Fraud Department (DLAF).

This leads to the next question of whether it is necessary to ensure that the existing administrative inspection/investigation authority/-ies at the level of the Member States should have the same scope of competences as OLAF. This would mean transposing the model at the EU level to the national level.

These issues cannot be left unresolved. First, answers are necessary in order to clearly determine the types of controls and control mechanisms that must be established at the level of the entire protection system. Second, they are necessary in order to facilitate the identification of the body/bodies that could act as an equal partner to OLAF and provide OLAF with adequate assistance in conducting its investigations. This would then be a huge contribution towards a much more effective implementation of Art. 12a of the amended OLAF Regulation on AFCOS. Likewise, this could contribute to the improvement of the legal framework under which administrative proceedings are regulated as well as to a much better cooperation, communication, and exchange of information between administrative investigative authorities.

We can turn to the 32nd Annual Report on the Protection of the European Union’s Financial Interests12 for an answer. Chapter 3 of the report reveals the complexity of the EU control framework with its multitude of players at the European and national levels. The report seemingly only considers managing authorities, paying agencies, audit authorities, and certifying bodies as part of the EU management and control system. Police forces, judicial authorities, and special (anti-fraud) bodies are listed as law enforcement authorities in the field of criminal prosecution. AFCOS is described as a coordinative authority that does not have investigative powers in most EU Member States.

For me as, a practitioner who has been involved in numerous discussions on the protection of the EU’s financial interests for a long time, the essential questions are: Which of these bodies could actually be considered an equal partner to OLAF and which of them should assist OLAF in conducting its administrative investigations? Which of them could even, in exceptional cases, conduct an investigation on behalf of OLAF?

As part of the management and control system of the EU funds, managing authorities, paying agencies, and certifying bodies certainly do not perform either administrative investigations or inspections. It should be stressed that their work could be controlled by OLAF and other competent EU authorities at the EU level. Furthermore, alerts about suspected irregularities and fraud can relate to the work performed by these authorities and abuses of power by the responsible persons in these authorities.

Police forces, judicial authorities, and special (anti-fraud) bodies as law enforcement authorities in the field of criminal prosecution can also not be fully considered equal partners to OLAF. They are set up to conduct criminal investigations and they are obviously more closely connected to the EPPO than to OLAF, which conducts administrative investigations only and operates within an administrative and non-criminal legal framework.

As regards the anti-fraud coordination services (AFCOS), it must be borne in mind that most services have an exclusive coordination role in their national systems and, as a rule, cannot also be considered to be an equal partner to OLAF at the national level. An exception may be constituted by the few services that were established in accordance with the OLAF model and that have the same scope of competence, including investigative powers, such as the Romanian DLAF.

The PIF report finally mentions customs authorities as a player in the EU’s control framework at the national level. However, customs authorities should not be seen as the only authority that conducts administrative investigations, since they relate to the revenue side only and do not cover expenditure control.

Taking into account this landscape, there is all the more the need to develop a clear overview of who the players are and who the players should be in the protection of the EU’s financial interests at the level of the Member States, in addition to determining what their role is and what it should be in the protection system. Moreover, it is important to clearly define which authority acts within the framework of administrative legislation and which authority acts within the framework of criminal legislation, since the boundaries can easily be crossed. Likewise, it is necessary to define a clear control framework for the EU’s financial interests, with clearly defined control mechanisms that should be established at the level of the entire system for the protection of these interests. Undoubtedly, measures must be avoided that would lead to unnecessary administrative burdens and be contrary to the primary goal of achieving a high level of protection of the EU budget.

V. Concluding Remarks

Challenging times are also marked by challenges for the EU and its 27 Member States, as they need to demonstrate their readiness and ability to respond to them adequately. At the same time, these challenges open up opportunities for progress in areas that have been so far been neglected and unexplored. In the field of the protection of the EU’s financial interests, the room for progress is quite extensive. It is very important to put in place appropriate, effective, and efficient anti-fraud mechanisms at all levels. Serious irregularities and especially fraud affecting the EU’s financial interests are complex, know no borders, and very often involve fraudsters operating in two or more Member States. The EU must show – and prove vis-à-vis its citizens – that it has established sufficient mechanisms to fight against all types of irregularities, fraud, and corruption, and that it is ready to continuously work on improving its anti-fraud policies. This necessitates adjustments to the time and the environment in which the policies are carried out, as well as compliance with the control mechanisms at the Member States’ level.

Currently, national authorities have to deal with administrative and criminal law systems that (significantly) differ from one country to another, with lengthy procedures for administrative and judicial cooperation, language barriers, a lack of resources, different priorities, etc. In order to be able to establish an efficient system for the protection of the EU’s financial interests, the competent national authorities need to have a robust understanding of the judicial and administrative frameworks in all EU Member States. In practice, this is regrettably not always the case.

The recent crises (the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters hitting individual Member States, and war conflicts), have shown quite plainly that the EU indeed needs to react quickly. However, we must keep in mind that our job is far from over at this point – there is still a lot to be done.

Council Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2093 of 17 December 2020 laying down the multiannual financial framework for the years 2021 to 2027, O.J. L 433I, 22.12.2020, 11.↩︎

The budget includes the European Development Fund.↩︎

Council Regulation (EU) 2020/2094 of 14 December 2020 establishing a European Union Recovery Instrument to support the recovery in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis, O.J. L 433I, 22.12.2020, 23.↩︎

Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 883/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 September 2013 concerning investigations conducted by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1073/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Council Regulation (Euratom) No 1074/1999, O.J. L 248, 18.9.2013, 1 as amended by Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2223 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 December 2020 as regards cooperation with the European Public Prosecutor’s Office and the effectiveness of the European Anti-Fraud Office investigations, O.J. L 437, 28.12.2020, 49.↩︎

Chapter VI of Council Regulation (EU) 2017/1939 of 12 October 2017 implementing enhanced cooperation on the establishment of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (‘the EPPO’), O.J. L 283, 31.10.2017, 1.↩︎

Cf. <https://www.eppo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-07/Working_arrangement_EPPO_OLAF.pdf> accessed 8 November 2022. See also eucrim 2/2021, 80.↩︎

The report is available at: <https://anti-fraud.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-09/olaf-report-2021_en.pdf> accessed 8 November 2022. See particularly pp. 37 et seq.↩︎

Available at: <https://www.eppo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-03/EPPO_Annual_Report_2021.pdf> accessed 8 November 2022.↩︎

Directive (EU) 2017/1371 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2017 on the fight against fraud to the Union’s financial interests by means of criminal law, O.J. L 198, 28.7.2017, 29.↩︎

The European Commission makes detailed recommendations to candidate countries on the system for the protection of the EU’s financial interests within the negotiation chapters. These recommendations are much broader than the legislative framework that is binding for the EU Member States.↩︎

The establishment and tasks of AFCOS are prescribed in Art. 12a of the amended OLAF Regulation, op cit. (n. 4).↩︎

Available at: <https://anti-fraud.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-11/pif_report_2020_en.pdf> accessed 8 November 2022.↩︎

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and are not an expression of the views of her employer.

https://doi.org/10.30709/eucrim-2022-015

//

https://doi.org/10.30709/eucrim-2022-015

//