Seven Arguments in Favour of Rethinking Corruption

Abstract

The act of “rethinking” corruption is necessary due to a global stagnation after more than two decades of international anticorruption efforts. The issue of corruption is being reframed as a security issue, rather than a developmental one, but the role international agency play in changing a country is still prominent. This article sums up the lessons learned from theoretical and practical advances outlined in the author’s book on “Rethinking Corruption.” It makes a clear argument in favour of rethinking corruption outside the traditional framework and offers a forecasting method, alongside state-of-the-art analytical, fact-based tools to map, assess, and predict corruption risks.

The author argues that corruption is a policy issue frequently overriding individual choice, and can only be tackled by strong policy interventions. She explains the limits of international intervention and demonstrates how much unfinished business was left behind by the developmental approach to anticorruption – business that can only be tackled domestically by pro-change coalitions. Evidence is shown that corruption has not decreased despite unprecedented efforts. This is the case because the international context presently creates far more opportunities for corruption than it poses constraints. Few countries and international organisations have proven able to solve the social dilemma of corruption. The instruments to collect evidence for action have been as poor as conceptualisation, but progress has been made and can be used by domestic coalitions seeking to challenge a corrupt status quo.

The article outlines that “Rethinking Corruption” is a non-orthodox, yet state-of-the-art guidebook for policy makers, administrators, and practitioners looking to identify an effective way of approaching corruption, engaging in corruption issue policy analysis, designing actionable measurement, and building successful coalitions against systemic corruption.

I. Introduction

The UK-based academic publisher Edward Elgar publishing hosts a book series dedicated to the “rethinking” of various science and social science concepts. 2021 saw corruption on the agenda in a very timely manner: having spent the previous 30 years on the margins of social science, corruption has become one of the most prominent cross-disciplinary topic infusing both academic and policy debates. The choice of author appeared less obvious, as I – an expert who had already published extensively on this topic from many different angles – was picked to provide a fresh take. Corruption had featured in several of my books/works up until this point, including a textbook1, an impact evaluation of EU anticorruption policies throughout the years and across the globe2, a warning that corruption is “omnipresent” due to its subversion of innovation3, as well as a new, model-based non-perception corruption index4. Drawing on this work, my team created an interactive website for practitioners at <www.corruptionrisk.org> using objective (not perception-based) and action-able indicators for over one hundred countries, from causes of corruption to a forecast.

So, what more could I say to avoid repeating myself? I decided to follow the structure of the over 20 classes I had taught on corruption as a policy phenomenon – or, capturing it even better, anticorruption as a comprehensive policy meant to disable corruption – in Berlin from 2013 to 2023. Even in the developed European Union, over half the countries have serious domestic issues. The course taught developed its own analytical instruments for diagnosis, context analysis, stakeholder analysis, and cost effectiveness of corruption problems, culminating in the fundamental question: how to address corruption as a social dilemma?

This gave rise to my new book “Rethinking Corruption,” published in 2023, as part of the already mentioned Elgar series “Rethinking Political Science and International Studies.” In the final chapter, I wrote that the historical career of corruption as an international topic has been one of a permanent shifting of meanings and paradigms. Thus, the act of “rethinking” corruption has already taken place more than once, contributing more to a post-truth about corruption than to anything else, despite extraordinary insights from people like Elinor Ostrom, Douglass North, and Michael Johnston. That said, such moments of wisdom passed very quickly without generating practical knowledge. This is where we need to bridge the gap and “rethink” out of the “inefficient anticorruption” box. To realize the goal of the book “Rethinking Corruption”, that is to bridge the gap and "rethink" outside the box of "inefficient anti-corruption", it is necessary to analyze the seven main rethinking approaches in the book, each carrying a solid truth, which are summarized below.

II. The Rethinking Approaches

1. A policy problem should not be conceptualized at the individual level.

There is evidence that, despite a widespread discourse in favour of “contextual” explanations, corruption and anticorruption are still conceptualized at an individual level. And this is wrong. Corruption control, or the capacity of a state to operate autonomously from private interests and for the greatest possible social welfare, is a social context. Corruption is a policy problem because individuals tend to follow the rules of the game of their respective societies (and organisations. The recent behaviouralist approach to corruption as an individual choice – without being necessarily wrong – applies only to a handful of situations (where corruption is an exception), and nowhere else. If we accept the evidence that individual choice is largely dependent on the social context, we in fact agree that little individual choice exists, and policies are needed far more than prosecutions. We need to change collective incentives, not individual ones, and so we need to stop asking how to nudge individuals into honesty as if the context surrounding them were one of integrity.

2. Corruption results from a balance between opportunities and constraints.

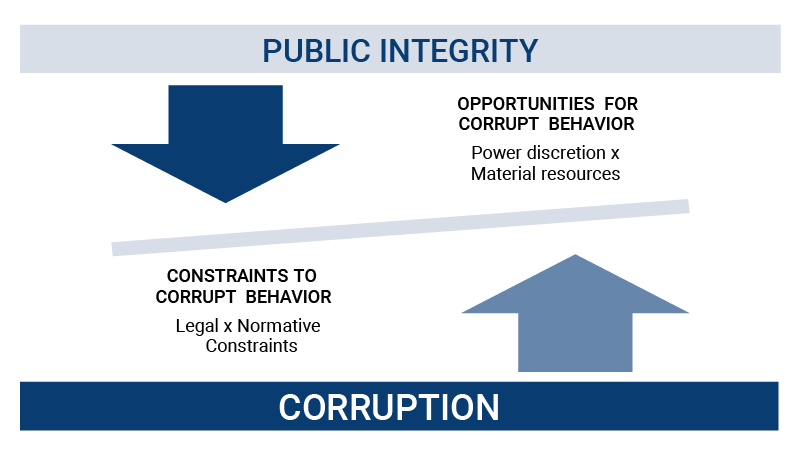

The second “rethinking” is needed to acknowledge that the literature on causes of corruption5 allows, at national level, to extend the individual level formula of Gary Becker6 on crime and treat corruption, for all practical and theoretical purposes, as a balance between opportunities (enablers) and constraints (disablers) in every social context. The classic model of the individual decision to engage in a criminal (corruption) act after a rational calculation of the probability of detection versus the opportunity of a crime is largely dependent on how this balance between opportunities and constraints plays out in the broader social context. Corruption control can thus be conceived as a balance (see Figure 1) between opportunities (power asymmetry and potential material spoils) and constraints that an autonomous society is able to force on the ruling elites through an independent judiciary, free media, and a mass of enlightened citizens who put up a strong demand for good governance.7

Figure 1. Control of corruption as a balance.

When a program like UN Oil for Food is designed without any constraints and multiple opportunities, we can expect systematic corruption, regardless of the nationality and culture of those involved in it. If we continue to aim anticorruption approaches at individuals, ignoring the broader balance (in a sector, activity, or a country), the overall prevalence of corruption will stay the same, although some individuals or groups of profiteers may be replaced by others when exposed.

3. A good corruption theory is action-able.

Using a model of opportunities versus constraints allows a better understanding and monitoring of corruption over time, as well as an assessment of the impact of anticorruption measures. Designing actionable instruments based on such a model enables us to see where countries fall short and identify what is missing to redress the balance, especially by comparing them with their regional or income peers. The European Research Centre for Anticorruption and State-Building (ERCAS) has developed instruments, like the Transparency Index (T-Index), and analytical tools, like the Index of Public Integrity (IPI), which provide an assessment able to capture any significant policy intervention which has an impact. In particular, the IPI allows us to measure the different elements of context which interact to create a society’s capability (or lack thereof) to control corruption. It identifies proximate measures for factors identified in research as impacting corruption risk, and provides mostly objective and actionable data to measure corruption control.8

4. Corruption is subversive for any political system

Corruption subverts any political system, autocracies and democracies alike. Consequently, it should not be seen as a prime factor for democratic backsliding, but rather as a vulnerability, jointly with concentrated economic rents, (such as mineral resources or drugs). Democracies that manage to solve the problem of corruption are the most resilient political systems in the world, but both overcoming corruption issues and sustaining the equilibrium do not come easily. This needs a high degree of cooperation in a society to solve collective action problems in order to uphold general welfare versus specific groups one (as we see in the successful lobby of many industries, like pharma, oil, etc). A repressive anticorruption approach – top-level prosecutions, special power investigators, special courts – has proven more of a danger for opposition politicians (as they offer authoritarian incentives for those who control them) than a tool to help democracies progress. Few countries have sufficient rule of law to clear individuals wrongfully accused of corruption and demand that the officials who fabricated evidence be prosecuted instead.9

5. The balance in international affairs has long been bending towards corruption.

A fifth point when rethinking corruption is that international factors, such as globalisation, the international anticorruption regulation such as the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), and external anticorruption interventions in various countries (e.g., Kosovo, Iraq, Guatemala, Afghanistan), have not succeeded in bringing corruption under control. The main reason for this is that opportunities for corruption in the global world by far exceed constraints when clear jurisdictions and normative constraints are lacking. Free trade alone is no match for the sovereignty of corrupt governments and the need to do business with them. With a new realism paradigm taking hold worldwide, we should at least acknowledge that the previous phase of norm socialisation only succeeded at a de jure, and not a de facto level. The UNCAC has not changed any country struggling with corruption (just as the UN has not been able to promote universal human rights practices). That is not to say that the creation of a universal set of integrity norms has been in vain, especially since citizens of most countries identify with values of ethical universalism. It only means that citizens (and their associations10) – and they alone – can help advance the transition from legal ethical universalism to its practice.

6. Solving corruption often means solving collective action problems.

The sixth reconsideration refers to the issue that a collective action problem exists whenever corruption is systemic, at national and other levels (e.g., FIFA or the oil industry). In general, a collective action problem is the result of clashing individual and collective best interests. As far back as in 1965, Mancur Olson described the underlying reasons for the observed lack of collective action for common interests in certain contexts. He argued that when individuals believe they can receive the benefits of cooperation without having to contribute to the cost, they are more likely to opt to free ride on the efforts of others.11 This is the central problem of collective action. According to Olson, a society will never be able to overcome it unless deliberate measures are put in place that incentivise groups to engage in collective action for the common interest, and not just pursue self or group interests. In corrupt contexts, principal agent tools fail due to the classic problem of absent political will – the principal is corrupt himself and the agent is not defecting: they both collude (i.e., politician and his political appointee, the civil servant into extracting private profit from public resources). The citizens are ineffective principals in their turn because they do not cooperate into forming an anticorruption party, but prefer to cut individual deals in their own selfish interest, therefore perpetuating a corrupt system. In this sense, human anticorruption agency has to be conceived of in broader terms, as only coalitions of interested parties, of which some are altruistic enough to make an initial investment (i.e., volunteer funds or work to enable others getting together), might be able to trigger substantial change if they manage to outnumber those who profit from the status quo. Outsiders (in the form of foreign donors or UNCAC peer review missions) may find a role for themselves in providing this initial investment on behalf of anticorruption domestic actors. However, success stories on changing systemic corruption are mostly rooted in domestic agency. Consequently, international intervention (where this is possible without unintended consequences, as otherwise it is ill advised to interven to clean other people’s countries altogether) – would be well advised to support broad national anticorruption coalitions rather than just governments, as the ownership of anticorruption should lie with citizens, and not kleptocrats.

7. Let’s not abandon anticorruption for development in favor of anticorruption for security.

My seventh and last issue of rethinking anticorruption strategies relates to the emergence of corruption as a security threat that replaced the more benevolent (though patronizing) view of corruption as a threat to development. In the 1980s anticorruption (as chaired by the World Bank) was an effort of reforming countries. After 9/11, many discovered that foreign individuals could detonate bombs in Western cities, rather than just acquiring soccer clubs or laundering their ill-gotten gains, as they had done before. Yet, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we witnessed Russian oligarchs treated as terrorists had once been and the new instruments of global anticorruption became the sanctions.

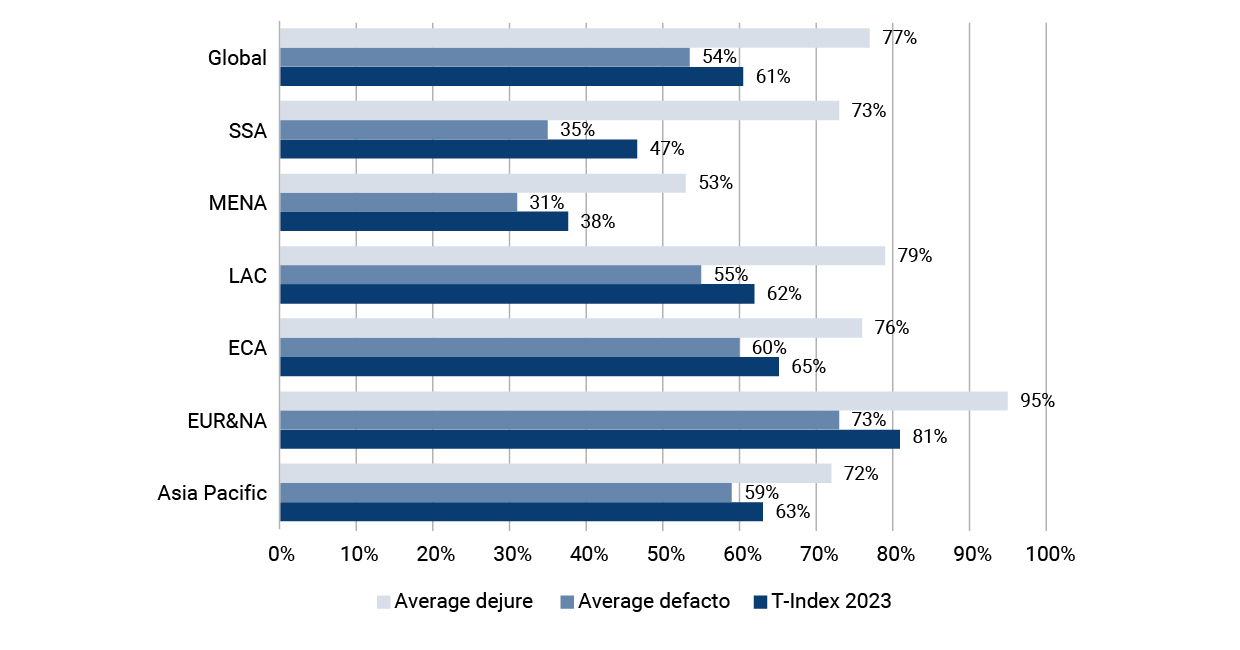

But moving into an old paradigm while our earlier work is to a large extent unfinished is not productive. The earlier antiterrorism measures have led to some progress in making international finance more transparent, narrowing down the grey and black areas (for instance in banking) .At country level, however, reforms were limited and transparency remains an unfinished job. The world has not yet exhausted transparency as a tool to prevent corruption, as the ERCAS T-Index shows (Figure 2).12

Figure 2. State of transparency: legal, real, and implementation gap.

The ERCAS’ T-index (that covers 140 countries) shows an important gap between the legal commitments made by governments (transparency de jure) and their actual implementation (transparency de facto). The survey confirmed that putting democratic transparency into practice may demand more than the simple ratification of treaties and adoption of laws. The way forward for any country is not more formal adoption of tools, but the implementation of these tools and granting citizens, the media, and civil societies the freedom to use them. Should this not be the main job, changing the rules of the game, rather than the attention-grabbing chasing after kleptocrats – some of which pose no danger to the global world order and stability, and they are often not indicted or cleared by the Courts, including European Courts, as in the case of assets freezing of former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych.

III. Conclusion

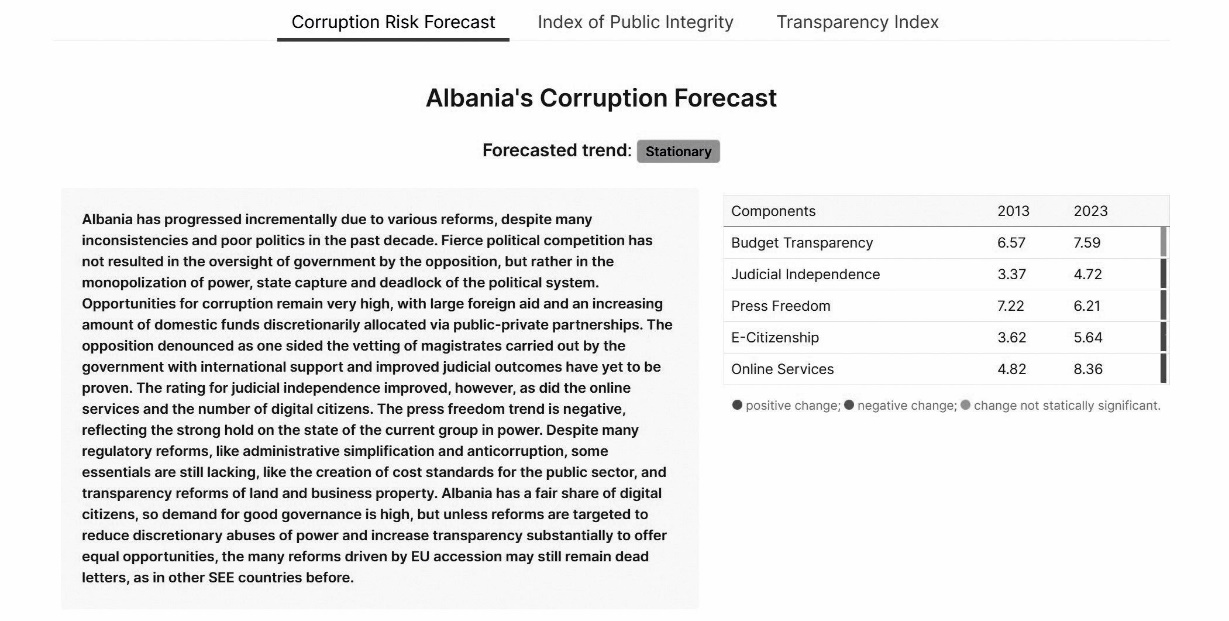

Finally, my team’s research offers several instruments to analyse corruption both as a market and as a government failure. Ultimately, these instruments are brought together in an analytical forecast designed to overcome the lack of sensitivity and concreteness of corruption indicators: the Corruption Risk Forecast. Once we have established a model of the main factors causing corruption as shown in Figure 1 (enablers and disablers), the trends can be followed over time to understand why a country changes (or not).13 To trace the evolution of corruption control, the Corruption Risk Forecast uses the disaggregated components of the Index for Public Integrity and observes the changes recorded since 2008. The Corruption Risk Forecast rates change as consistent when a country has progressed (or regressed) regarding three indicators (two of them, e-services offered by the state and e-citizens, individuals with a broadband Internet connection are bound to grow naturally) and has not regressed (or progressed) in any of the other three indicators. Subsequently, the Corruption Risk Forecast checks for inconsistencies regarding political change and societal demand. This trend analysis and weighting produces three categories of countries: stationary cases, improvers, and backsliders. Figure 3 illustrates this assessment with the case of Albania. The figure shows Albania progressing in three indicators (Judicial Independence, E-Citizenship, and Online Services), regressing in one (Press Freedom) and stagnating in one (Budget Transparency). Thus, following our assessment, Albania’s change is rated as not consistent, and categorized as stationary.14

Figure 3. Corruption Forecast for Albania

Source: https://www.corruptionrisk.org/country/?country=ALB#forecast

The forecast can serve as an evaluation tool for a country’s anticorruption strategists, as well as for a longer-term diagnosis complementing the Index for Public Integrity, which offers only a snapshot at any moment in time. It is important to understand a country’s trend to confirm or adjust the anticorruption strategists’ theory of change and strategy accordingly. Our complete datasets can be found on https://corruptionrisk.org/datasets/.

A. Mungiu-Pippidi, The Quest for Good Governance, Cambridge University Press, 2015.↩︎

A. Mungiu-Pippidi, Europe's Burden: Promoting Good Governance across Borders, Cambridge University Press, 2019.↩︎

A. Mungiu-Pippidi, “Corruption: Good governance powers innovation”, Nature 518, 295–297(2015).↩︎

A. Mungiu-Pippidi, “The time has come for evidence-based anticorruption”, (2017) 1 Nature Human Behaviour, Article number 0011.↩︎

D. Treisman, “What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research?” (2007) 10 Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci., 211-244.↩︎

G.S. Becker, “Nobel lecture: The economic way of looking at behavior”, (1993) 101 (3) Journal of political economy, 385-409.↩︎

See also G. Becker, “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach”, (1968) 76 Journal of Political Economy, 169–217; J. Huther and A. Shah. Anticorruption Policies and Programs: A Framework for Evaluation, Policy Research Working Paper 2501, The World Bank, 2000.↩︎

For a full explanation of the IPI methodology, see <https://corruptionrisk.org/ipi-methodology/> accessed 23 January 2024.↩︎

An example is Botswana, cf. <https://freedomhouse.org/country/botswana/freedom-world/2022> accessed 23 January 2024.↩︎

NGOs, anticorruption networks, political parties against corruption, etc.↩︎

M. Olson Jr., The Logic of Collective Action, Harvard Economic Studies 124, 1965.↩︎

In 2021, ERCAS measured the state of transparency regarding accountability in the new T-Index (computer mediated government transparency) for 129 countries for the first time by direct observation. The methodology and the first results appeared in Regulation and Governance in 2022, and a new webpage created a fully transparent index, where every item could be traced back to the original webpage with one click, and readers could use a feedback button to report errors. The T-Index benefits from the digitalisation of transparency and does two innovative things: First, it measures the type of transparency most relevant for anticorruption and rule of law. Second, to this end, it distinguishes between de jure (legal commitments) and de facto (already implemented transparency) and observes the latter directly, as digital transparency.↩︎

We use the disaggregated components of IPI, without normalisation (just recording their original scales to 1–10, with 10 being best control of corruption), and we observe changes since 2008, considering them significant if they are above the average global standard deviation of average change. See <https://www.corruptionrisk.org/forecast/> for full methodology and results.↩︎

See additionally <https://www.corruptionrisk.org/forecast-methodology/>.↩︎