The Directive on the Right to Legal Aid in Criminal and EAW Proceedings Genesis and Description of the Sixth Instrument of the 2009 Roadmap

Abstract

The article traces how Directive (EU) 2016/1919 on legal aid—adopted 26 Oct 2016—completed the 2009 Procedural Rights Roadmap. It recounts why “measure C” (access to a lawyer + legal aid) was split, the Commission’s 2013 proposal (initially focused on provisional legal aid), and the political split between “northern” states seeking flexibility/cost control and “southern” states/Parliament pushing broader coverage. After trilogues (2015–16), a compromise replaced “provisional” with legal aid, set a scope of “deprivation of liberty plus” (also covering mandatory-lawyer situations and key investigative acts), and anchored eligibility in combined means and merits tests, with a safety net guaranteeing aid when detention is decided or ongoing. The Directive also covers EAW proceedings, and adds rules on decisions, quality, and training. Member States must transpose by 25 May 2019.

I. Introduction

On 26 October 2016, the European Parliament and the Council adopted Directive (EU) 2016/1919 on legal aid for suspects and accused persons in criminal

proceedings and for requested persons in European Arrest Warrant proceedings. The Directive is the sixth legislative measure that has been brought to pass since the Council adopted its Roadmap on procedural rights seven years ago.

The Directive, which completes the roll-out of the Roadmap,1 was a difficult measure to negotiate in view of its potentially considerable financial implications. The final text of the Directive has been welcomed by practitioners, academics, and other interested parties. This article describes the genesis of the Directive and provides a description of its main contents.

II. Genesis of the Directive

1. Roadmap for strengthening procedural rights

On 30 November 2009, on the eve of the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the Council (Justice and Home Affairs) adopted the Roadmap for strengthening procedural rights of suspected or accused persons in criminal proceedings.2 The Roadmap provides a step-by-step approach3 – one measure at a time – towards establishing a catalogue of procedural rights for suspects and accused persons in criminal proceedings. The Roadmap pursued the following aims:

Strengthen mutual trust between the judicial authorities in the Member States of the European Union (EU), by setting minimum rules on procedural rights across the EU.

Foster the application of the principle of mutual recognition of judicial decisions, in accordance with Art. 82(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU), for example in the context of the Framework Decision on the European Arrest Warrant (EAW)4 and the Directive on the European Investigation Order.5

Improve the balance between the measures aimed at facilitating prosecution and sentencing, on the one hand, and the protection of procedural rights of the individual, on the other.

The Roadmap calls on the Commission to submit proposals for legislative measures on various procedural rights (measures A to E). Subsequent to its adoption, the Roadmap has been gradually rolled out. By 25 October 2016, five measures had been adopted: Directive 2010/64/EU on the right to interpretation and translation,6 Directive 2012/13/EU on the right to information,7 Directive 2013/48/EU on the right of access to a lawyer,8 Directive (EU) 2016/343 on the presumption of innocence,9 and Directive (EU) 2016/800 on procedural safeguards for suspected or accused children.10

2. Split of measure C

Measure C as foreseen in the Roadmap addressed two issues: legal advice and legal aid. The short explanation in the Roadmap provided that "the right to legal advice (through a legal counsel) for the suspected or accused person in criminal proceedings at the earliest appropriate stage of such proceedings is fundamental in order to safeguard the fairness of the proceedings; the right to legal aid should ensure effective access to the aforementioned right to legal advice."

However, in its proposal for a Directive in relation to measure C, which the Commission presented in June 2011, the aspect of legal aid had been left out.11 The proposal only dealt with the issue of legal advice, or, in the terms of the proposal, with the right of access to a lawyer.12 As regards the issue of legal aid, the Commission observed that this issue warranted a separate proposal "owing to the specificity and complexity of the subject."13

In a ministerial letter of September 2011, five Member States14 expressed misgivings about the fact that the Commission’s proposal on the right of access to a lawyer did not set rules on legal aid. 15 According to these Member States, "[t]he two issues were joined in a single measure in the Roadmap on procedural rights, (…) reflecting that Member States envisaged these matters being dealt with jointly." They underlined that "[a]ny directive on the right of access to a lawyer should take into account the consequential costs and implications for Member States’ legal aid systems."

In order to deal with the concerns of the five Member States, which were supported by some other Member States, two steps were taken in the context of the discussions on the draft Directive on access to a lawyer:

Firstly, the text as proposed by the Commission was modified. Although the Commission’s proposal for a Directive on access to a lawyer did not include (detailed) rules on legal aid, it provided that Member States should not apply less favourable conditions to legal aid covering instances where access to a lawyer was granted under the Directive, compared to instances where access to a lawyer was already available under national law.16 Obviously, this provision could have had substantial financial implications in cases in which the Directive were to provide a wider right of access to a lawyer than already available under national law. The Council therefore decided to delete this provision. In relation to legal aid, the final text of Directive 2013/48/EU now only provides that "[t]his Directive is without prejudice to national law in relation to legal aid, which shall apply in accordance with the Charter and the ECHR."17

Secondly, the Member States sought and obtained further guarantees from the Commission that it would indeed present a proposal on legal aid. When the Council reached a general approach on the Directive on access to a lawyer, in June 2012, several declarations were tabled. In one declaration, the Council and the European Parliament called on the Commission "to present a legislative proposal on legal aid at the earliest." The Commission replied by a separate declaration, in which it stated having "the intention to present a proposal for a legal instrument on legal aid in the course of 2013, in accordance with the Roadmap."18 Although this guarantee was not watertight, the Member States were satisfied with it.19

In its declaration, the Commission purposely used the term "legal instrument" instead of "legislative proposal." Since the issue of legal aid was considered to be very sensitive and difficult, the Commission wanted to keep the possibility open of presenting a proposal for a non-legislative instrument, such as a recommendation, instead of a proposal for a directive. Although the Roadmap explicitly foresees that action on procedural rights cannot only comprise legislation but also "other measures," various stakeholders would certainly have been disappointed if the Commission had taken that line of course. Fortunately, however, this was not the case.

3. The Commission proposal – Mixed reception

On 27 November 2013, the Commission issued its "Proposal for a Directive on provisional legal aid for suspects or accused persons deprived of liberty and legal aid in European arrest warrant proceedings."20 The proposal was part of a package of three legislative proposals on procedural rights,21 and it was accompanied by a Commission recommendation.22

During a meeting on 10 December 2013, organised by ERA (Academy of European Law), the Commission presented its procedural rights package and discussed it with practitioners and policy stakeholders, such as the ECBA, Fair Trials, and Justicia. While the other two legislative proposals (on the presumption of innocence and on procedural safeguards for children) were generally received positively, the proposal for a Directive on legal aid got a mixed reception. There was praise for the fact that the Commission had presented a legislative proposal on this complicated issue, but various concerns were raised, such as in relation to the scope of the proposed Directive. Disappointment was also expressed over the fact that various elements had been included in the non-binding Commission recommendation, since it was felt that they belong in the binding Directive.

4. Discussions in the Council – General approach

The Member States did not discuss the Commission proposal during the first six months after its presentation by the Commission. During this period, however, Ireland and the United Kingdom indicated that they would not participate in the adoption of the Directive, in application of Protocol No. 21 to the Lisbon Treaty. Denmark did not participate either, as it never does nowadays in the area of freedom, security and justice, in accordance with Protocol No. 22 to the Lisbon Treaty.

The discussions in the Council on the proposed Directive started under Italian Presidency (second semester of 2014). The Member States quickly established "like-minded" groups, which held informal meetings to coordinate their positions. The Member States in such groups did not necessarily share the same views on all points of the proposed Directive, but they formed coalitions to support each other during the discussions.

A like-minded group of (mostly) northern Member States sought to reduce the scope of the Directive and make the text more flexible. They not only had concerns about the financial implications of the text as proposed by the Commission but also concerns of a practical and principle nature, as they felt that legal aid should not necessarily always be available in relation to minor and less serious offences, such as shoplifting of goods of little value. They therefore proposed excluding certain minor offences from the scope of the Directive and inserting a proportionality clause into the text.

While a majority of Member States supported or could accept the ideas of the group of northern Member States, these ideas were not shared by a like-minded group of (mostly) southern Member States, including Italy. Therefore, the Italian Presidency decided not to push for a general approach23 during its term in office.

Under the Latvian Presidency (first semester of 2015), the Council quickly reached a general approach on the basis of the line advocated by the group of northern Member States.24 At three places in the text, however, the Commission and members of the group of southern Member States25 formally indicated that they did not agree. In a statement, seven Member States considered that the text of the draft Directive as set out in the general approach would not allow achievement of the aim of enabling all European citizens to enjoy a practical and effective exercise of the right of access to a lawyer, as enshrined in Directive 2013/48/EU. The Member States indicated, however, that they had decided not to oppose the general approach so as to allow the legislative process to go further and start discussions with the European Parliament and the Commission in the context of the trilogues.26

Usually in the Council, a lot of efforts are made with a view to ensuring that all Member States are able to accept EU legislative texts. This holds particularly true for the area of EU criminal law, which is considered to be very sensitive (compare the exceptions made for this area of law in the Lisbon Treaty). It was therefore quite exceptional that, in this case, a general approach was reached by overriding the strong objections of several Member States. However, this overriding of objections seemed tougher than it actually was, because the legislative process was only half way, and the Member States concerned knew perfectly well that the Commission and the European Parliament generally supported their line of thinking. Consequently, it was very likely that the text of the Directive would be modified in a way that would be more acceptable to them.

The above division between the Member States on the text of the general approach was clearly conveyed to the public, and the European Parliament was very much aware of it. This made for a curious start to the negotiations between the Council and the European Parliament.

5. Discussions in the Parliament’s LIBE Committee – Orientation vote 27

In the meantime, the LIBE Committee of the European Parliament had appointed Dennis de Jong (NL, Confederal Group of the European United Left − Nordic Green Left) as its rapporteur (first responsible Member). He had to obtain a mandate, on behalf of the European Parliament, for negotiations with the Council. This was not an easy task, since the MEPs in the LIBE Committee, like the Member States in the Council, were rather divided on this file: while some MEPs (or political parties) took an "idealistic" approach, others preferred taking a more "realistic" one, by following the rationale of the Commission or even going in the direction of the Council.

The "idealistic" MEPs, guided by Mr. de Jong, felt that the Commission proposal lacked ambition. They particularly felt that the scope of the proposed Directive on legal aid should be extended and aligned "one-on-one" with the scope of Directive 2013/48/EU on access to a lawyer.

After intense discussions that lasted several months, Mr. de Jong was able to secure a large majority of MEPs behind his position.28 As a consequence, the European Parliament, represented by Mr. de Jong, entered into negotiations with the Council with a strong and ambitious mandate.

Whereas the Council in its general approach had reduced the scope of the Commission proposal, the LIBE Committee had substantially enlarged this scope in its orientation vote. It therefore did not seem easy to reach a compromise between the co-legislators during the trilogue negotiations.

6. Trilogue negotiations under Luxembourg Presidency

The negotiations between the Council and the European Parliament, assisted by the Commission as "honest broker", started under the Luxembourg Presidency (second semester of 2015). Contrary to the work in other files, no technical meetings involving civil servants of the three institutions were held in respect of the proposed Directive. The rapporteur of the European Parliament was namely of the opinion that during negotiations between the institutions, all work should be carried out in trilogues (i.e., in the presence of the rapporteur and often also of one or more shadow rapporteurs). This position did not pose any problem as regards the draft Directive on legal aid, which was a small instrument of a rather political nature.

At the beginning of the negotiations, not much progress was made. The rapporteur defended the Parliaments position, stating that the scope of the Directive on legal aid should be aligned with the scope of the Directive on access to a lawyer, since access to justice should be equally available to all, whether rich or poor. He underlined that access to justice would also be in the interest of the Member States, as it could avoid miscarriages of justice.

On behalf of the Council, the Luxembourg Presidency objected that, in times of financial constraint, the Member States could not permit themselves to have legal aid systems in place that are too expensive. The Presidency observed that, according to the Member States, accepting the wishes of the European Parliament to broaden the scope of the Directive would result in unacceptable additional financial burdens for them.

The rapporteur asked the Presidency to provide data, including an estimation of the financial implications of the wishes of the European Parliament, so that he could verify whether putting these wishes in place would indeed lead to such unacceptable additional financial burdens. The Presidency forwarded this question to the Member States.29 While some answers were given,30 it appeared impossible to elicit a complete answer from the Member States to the said question.

On suggestion of the rapporteur, the European Parliament then decided to ask its competent services31 to make an impact assessment in order to evaluate, i.a., what the financial implications would be if Parliament's wishes for enlargement of the scope of the Directive were to be put in place. The Council and the Commission were a bit surprised by this move, since it meant that work on the Directive could be delayed for several months (until April 2016, when it was expected that the impact assessment would be available). This was one of the reasons why it was not possible to reach an agreement on the Directive under the Luxembourg Presidency.

7. Trilogue negotiations under the Netherlands Presidency

As from January 2016, the Netherlands held the Presidency of the Council for the first semester of 2016. The Netherlands, which was perfectly aware of the complexities of the draft Directive, took a mixed approach. On the one hand, as the Presidency, it was eager to reach an agreement with the European Parliament on this file during its term in office. On the other hand, it was a member of the group of northern States and as such was anxious about ending up with a text that would have too broad a scope.

It was therefore understandable that, during bilateral meetings with the Member States, the Netherlands Presidency not only sounded Member States out about their concerns and possible red-lines on this file, 32 but also informally explored the possibility of generating a "light version" of the Directive. Such a version would consist in maintaining the provisions on legal aid in EAW proceedings, but postpone to the future the discussions concerning the provisions on legal aid in criminal proceedings (and possibly deal with them in the context of another legal instrument). This idea, however, was not received with much enthusiasm by the other Member States, which feared that their negotiation leverage would then be reduced, while the hot potato remained on the table.

While waiting for the outcome of the impact assessment of the European Parliament, rapporteur MEP Dennis de Jong and Jan Janus (Chair of the Council working party) decided to start their talks on the issue of legal aid in EAW proceedings. It immediately appeared that the chemistry between both players – two Dutchmen of roughly the same age – was excellent. Therefore, once they had swiftly made substantial progress on the issue of legal aid in EAW proceedings, they successfully went on to tackle other issues, such as training and quality of legal aid services. However, the issue of legal aid in criminal proceedings still remained pending, since the negotiators had agreed that they would only try to crack this nut after the impact assessment by the European Parliament services became available.

This was the case by the end of April 2016. Subsequently, the European Parliament held a "strategic meeting" to examine the impact assessment. The European Parliament distilled two conclusions from this document: a) the amendments proposed by the LIBE Committee in its orientation vote would enhance the protection of suspects and accused persons from a fundamental rights point of view; and b) the costs for Member States as a result of these amendments would increase but they would still be reasonable. 33

In the light of these conclusions, the Parliament discussed four options on the way forward.34 It decided to choose the second option, which meant that the Parliament accepted that the scope of the Directive on legal aid would not be aligned one-on-one with the scope of the Directive on access to a lawyer, while striving to improve the Commission proposal where possible. Hence, one could say that the Parliament went from an "idealistic" to a "realistic-plus" approach.

On this basis, the parties resumed negotiations at the beginning of May 2016. In view of the little time remaining before the end of the Netherlands Presidency, the negotiating parties had a busy schedule in order to reach full agreement on the text of the Directive. During this process, they received considerable support from Ard van der Steur, who was the Dutch Minister of Justice.35

8. Agreement

On 23 June 2016, at the ninth trilogue, the negotiating parties reached a provisional agreement on the text of the Directive. After having received the assurance that this text was agreeable to a (large) majority of political groups in the European Parliament, the Presidency submitted it to the Council's Permanent Representatives Committee (Coreper).36 On the last day of the Netherlands Presidency, 30 June 2016, Coreper almost unanimously37 confirmed that the text was acceptable to the Council.

After legal-linguist revision, the text of the Directive was formally adopted on 26 October 2016, and it was published as Directive (EU) 2016/1919 in the Official Journal of 4 November 2016. According to its Art. 12, the Member States are obliged to implement the Directive into their national legal orders by 25 May 2019.

III. Description of the Main Elements of the Directive

Directive (EU) 2016/1919 on legal aid is rather small. It contains two main articles: Art. 4 on legal aid in criminal proceedings and Art. 5 on legal aid in EAW proceedings, which have to be read together with Art. 2 on the Directive’s scope. Moreover it contains two accessory provisions, which may however prove to be of considerable value: Art. 6 on decisions regarding the granting of legal aid, and Art. 7 on the quality of legal aid services and training. These provisions will be described below, after brief consideration of Art. 1 concerning the subject matter.

1. Subject matter

The purpose of the Directive is to ensure the effectiveness of the right of access to a lawyer provided for under Directive 2013/48/EU, by making available the assistance of a lawyer funded by the Member States for suspects and accused persons in criminal proceedings and for requested persons in EAW proceedings.38

According to its Art. 1(2), nothing in the Directive should be interpreted as limiting the rights provided for in Directive 2013/48/EU on access to a lawyer and in Directive (EU) 2016/800 on procedural safeguards for children. In relation to the Directive on access to a lawyer, the aim of this provision is notably to underline that the smaller scope of the legal aid Directive, compared to the Directive on access to a lawyer, does not in any way affect the rights provided for under the latter Directive.

As regards the Directive on safeguards for children, the provision is of even more relevance, since that Directive provides a self-standing right for children to be granted legal aid in certain circumstances.39

2. Legal aid in criminal proceedings

a) Searching for added value: provisional legal aid

In its proposal for a Directive, the Commission had suggested setting rules for provisional legal aid in criminal proceedings (and in EAW proceedings). Provisional legal aid would be a kind of emergency legal aid of a temporary nature that Member States should grant when suspects or accused persons are deprived of liberty. According to the Commission, the right to provisional legal aid should last until the competent authority has taken the final decision on the eligibility of the suspect or accused person for (ordinary, regular) legal aid. The Member States could recover provisional legal aid granted to suspects or accused persons if, following the final decision on the application for legal aid, the person concerned would not, or would only partially, be eligible for legal aid under the Member State's legal aid regime.

In order to explain the choice for setting rules on provisional legal aid (instead of ordinary or regular legal aid), the Commission observed that other instruments of European and international law already provide rules on the right to legal aid in criminal proceedings, such as the Charter (Art. 47(3)), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR, Art. 6(3)(c)), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, Art. 14(3)(d)). The Commission had therefore carefully assessed where the Directive could contribute "added value" to those existing rules and improve mutual trust between criminal justice systems, while taking into account the need for caution in times of fiscal consolidation. According to the Commision, it is in the early phase of criminal proceedings, especially when deprived of liberty, that suspects or accused persons are most vulnerable and are most in need of assistance by a lawyer and, hence, of financial assistance. It is for this reason that the Commission proposed setting up rules on provisional legal aid, thus ensuring that suspects and accused persons who are deprived of liberty receive assistance by a lawyer at least until the decision on (ordinary, regular) legal aid is taken. 40

The reasoning of the Commission, according to which the Directive should not copy existing rules but provide added value, is understandable. At the same time, it raises questions, since the application of this reasoning could put the existence of various Roadmap measures in doubt. It is true that procedural rights are also set forth in the instruments referred to by the Commission, notably the ECHR, as interpreted in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). The Roadmap Directives, however, provide detailed rules on procedural safeguards in binding legislative instruments (not, as is often the case in the ECHR context, in casuistic case law), the Member States are obliged to bring their national legislation in line with the Directives, and the TFEU provides powerful enforcement mechanisms in order to make sure that Member States will comply with the Directives. Therefore, the mere fact that rules on procedural rights − even if comparable to the ECHR and the case law of the ECtHR − are put in EU Directives, is added value in itself.

b) From provisional legal aid to legal aid

Many Member States expressed misgivings regarding the concept of "provisional legal aid," because they feared that it would heavily complicate their procedures and because they felt it to be redundant. They observed in this regard that they were used to taking decisions on legal aid within a (very) short time. Therefore, rather soon in the discussions in the Council, it was agreed to put a recital into the text, stating that "if Member States have a comprehensive legal aid system ensuring that the persons concerned can receive assistance by a lawyer without undue delay after deprivation of liberty and at the latest before questioning, this should be considered as complying with the obligations imposed by the Directive with respect to provisional legal aid."41

During the negotiations for a Council general approach, the incoming Latvian Presidency suggested abandoning the concept of "provisional legal aid" and referring simply to "legal aid." Although this suggestion was very sensible, it received little support, probably because the Member States felt that it would be advisable to discuss such substantial modification during the trilogues between the institutions.

For this reason, it came as no surprise that, during the negotiations between the Council and the European Parliament, when the latter requested that the Directive should simply deal with legal aid, the Netherlands Presidency had no difficulties in convincing the Member States to agree with this request, as part of a compromise package. As a consequence, Art. 4 of the Directive no longer refers to "provisional legal aid" anymore, but to "legal aid."

c) Scope

The scope of the right to legal aid in criminal proceedings has been subject to considerable change. The Commission proposed that this right should apply in respect of all suspects and accused persons who are deprived of liberty and who have the right of access to a lawyer pursuant to Directive 2013/48/EU.

As previously indicated, the European Parliament requested that the scope of the Directive on legal aid be aligned with the scope of the Directive on access to a lawyer, meaning that the Directive would apply to all suspects and accused persons, whether deprived of liberty or not (at large).

The Council, however, almost unanimously rejected this request. It observed in this context that the ECtHR in its case law attaches greater weight to deprivation of liberty42 and that the Directive on access to a lawyer obliges Member States only in relation to situations of deprivation of liberty to make the necessary arrangements, including legal aid if applicable, in order to ensure that suspects or accused persons are in a position to effectively exercise their right of access to a lawyer.43

A compromise was reached on a scope that could be defined as "deprivation of liberty plus." Apart from the situation in which suspects or accused persons are deprived of liberty, two other situations were identified to which the provisions on the right to legal aid in criminal proceedings should apply (Art. 2(1)):

1) when suspects or accused persons are required by law to be assisted by a lawyer ("mandatory assistance"), and

2) when such persons are required or permitted to attend certain investigative or evidence-gathering acts, including (as a minimum) identity parades, confrontations, and reconstructions of the scene of a crime. These acts, inspired by the case law of the ECtHR, were already specifically identified in the Directive on access to a lawyer and are also described therein.44

The addition of the category "mandatory assistance" was logical: if Member States provide in their national law that suspects or accused persons are required to be assisted by a lawyer, then the consequence should be that the rules on legal aid also apply. The obligation for mandatory assistance can also derive from EU law, in particular from the Directive on safeguards for children (see point 1 above).

Although the text on the scope seems a fair compromise, one could raise the question of whether it would not have been possible for the Member States to agree on a wider scope of the right to legal aid in criminal proceedings, including the situation in which suspects and accused persons are not deprived of liberty, in view of the provisions on eligibility as finally agreed (see below under d). Indeed, these provisions contain considerable flexibility for Member States, and it can happen that persons who are not deprived of liberty (anymore) are suspected or accused of having committed an offence of such seriousness or complexity that providing legal aid is merited. To be noted, however, that the Directive sets minimum rules: Member States are perfectly free to set higher standards and provide in their national law that, in certain circumstances, legal aid should also be provided to suspects and accused persons who are not deprived of liberty.

d) Eligibility - Means and merits test

The above-mentioned recommendation of the Commission45 contained extensive provisions on the issue of eligibility for legal aid in criminal proceedings. The European Parliament proposed transferring these provisions from the recommendation to the Directive. The Council could agree with that, since the suggestions were heavily inspired by the Charter and the ECHR, as interpreted in the case law of the ECtHR, which should be applied by the Member States anyway.

In the final text of the Directive, the basic rule on eligibility is almost a literal copy of Art. 47, third indent of the Charter, and of Art. 6(3)(c) ECHR: "Member States shall ensure that suspects and accused persons who lack sufficient resources to pay for the assistance of a lawyer have the right to legal aid when the interests of justice so require" (Art. 4(1)).

Hence, under the Directive, a suspect or accused person has the right to legal aid when two conditions are fulfilled:

a) lack of sufficient resources, and

b) the interests of justice must require legal aid to be provided.

In order to determine whether these conditions are fulfilled, the Member States may apply a means test, a merits test, or both (Art. 4(2)).

In the context of a means test, when Member States determine whether a suspect or accused person lacks sufficient resources to pay for the assistance of a lawyer, they should take into account all relevant and objective factors, such as the income, capital, and family situation of the person concerned, as well as the costs of the assistance of a lawyer and the standard of living in the Member State concerned (Art. 4(3)).

It is obvious that such a means test leaves ample discretion to the Member States to determine whether a person lacks sufficient resources and hence is eligible for legal aid (subject, possibly, to a merits test). However, if a person offers to prove his lack of sufficient resources and there are no clear indications to the contrary, it seems that the condition relating to lack of sufficient resources is fulfilled.46

In the context of a merits test, when Member States determine whether the interests of justice require that legal aid be provided, they should take into account the seriousness of the criminal offence, the complexity of the case, and the severity of the sanction at stake (Art. 4(4)). These criteria come straight from the case law of the ECtHR.47

The European Parliament requested adding a criterion relating to the social and personal circumstances of the person concerned. This was left out, however, because it was felt that it should be possible to exclude eligibility for legal aid in respect of certain categories of offences. Reference to that possibility has been made in the recitals, where it is written that "the merits test may be deemed not to have been met in respect of certain minor offences."48 In order to address the request of the European Parliament, a specific provision has nevertheless been inserted, obliging Member States to ensure that the particular needs of vulnerable persons be taken into account in the implementation of the Directive (see Art. 9). 49

e) Eligibility - safety net

Since the merits test, like the means test, leaves a large margin of discretion to the Member States, a safety net has been installed. According to this safety net, the merits test is considered to have been met in any event in the following two situations (Art. 4(4), second sentence):

(a) when a suspect or an accused person is brought before a competent court or judge in order to decide on detention at any stage of the proceedings within the scope of this Directive; and

(b) during detention.

Hence, as a result of this safety net, which is also laid down in the Directive on safeguards for children,50 the suspect or accused person should be granted legal aid if detention is at stake51 or if that person is in detention (subject, where applicable, to a means test).

"Detention" in this context has a restricted meaning: it refers to pre-trial (or provisional) detention, i.e., excluding post-trial detention, which refers to the period when a person serves a sentence. This is a result of the close link between the legal aid Directive and the Directive on access to a lawyer, which applies "until the conclusion of the proceedings, which is understood to mean the final determination of the question whether the suspect or accused person has committed the offence."52 Moreover, since the detention has to be ordered by a court or a judge, police custody and other similar forms of deprivation of liberty are excluded from this notion.

f) Legal aid to be granted in a timely manner

Legal aid has to be granted in a timely manner so that it produces the desired effects. In this context, the European Parliament insisted that legal aid be granted before suspects or accused persons are questioned by the police or by another competent authority, thus allowing such persons to be assisted by a lawyer prior to and during such questioning. It was agreed that the same holds true for certain investigative or evidence-gathering acts.

For this reason, the Directive provides that Member States should grant legal aid without undue delay and, at the latest, before questioning or before an investigative or evidence-gathering act, as referred to in Art. 2(1) of the Directive, is carried out (Art. 4(5)).

This provision obviously should not be interpreted as a self-standing provision obliging Member States to grant legal aid. One is invited to read the provision as if it is introduced with wording along the following lines: "When legal aid is to be granted in accordance with this Article, Member States shall ensure that such aid …".

In the recitals, it is provided that, if the Member States are not able to grant (ordinary, regular) legal aid in a timely manner, they should at least grant emergency or provisional legal aid before questioning or before investigative or evidence-gathering acts are carried out. This important clarification is a clear reference to the spirit of the original Commission proposal.53

2) Right to legal aid in EAW proceedings

a) Double right to legal aid in EAW proceedings

The Directive on access to a lawyer provides that a person who is subject to an EAW (requested person) has a double right of access to a lawyer once he has been arrested in the executing State. The requested person not only has the right of access to a lawyer in the executing State, but he also has the right to appoint a lawyer in the issuing State. The task of the latter lawyer is to assist the lawyer in the executing State by providing him with information and advice.54

In line with the Directive on access to a lawyer, the Commission proposed that requested persons should have the right to legal aid in both the executing State and the issuing State (if they appoint a lawyer in that State).

While the Member States could agree to the provisions on legal aid in the executing State, a majority of them was against the provisions on legal aid in the issuing State. According to these Member States, the strictly ancillary role of the lawyer in the issuing State would not justify such provisions. They also observed that introducing a right to legal aid in the issuing State could give rise to a number of practical issues, e.g., how the payment of the two lawyers would be claimed and organised, how the costs should be distributed, issues of communication, etc. For this reason, in its general approach, the Council deleted the provisions relating to legal aid for the lawyer in the issuing State.

During the trilogue negotiations, the European Parliament and the Commission put the issue back on the table. They put forth, i.a., that the budgetary implications of the provisions for the Member States would be somewhat reduced, in view of the small number of EAW cases.

The Netherlands Presidency put considerable pressure on the Member States to show flexibility on this point, since it knew that some kind of concession would be a conditio sine qua non for the European Parliament (and the Commission) to reach a deal.

In the end, the Member States reluctantly accepted inserting provisions on legal aid for the lawyer in the issuing State into the text, but subject to two conditions (Art. 5(2)):

a) the provisions on legal aid for the lawyer in the issuing State should only apply to EAWs issued for the purpose of conducting a criminal prosecution, and

b) legal aid should only be provided "in so far as such aid is necessary to ensure effective access to justice".

As a result of the condition under a), the provisions on legal aid for the lawyer in the issuing State do not apply to EAWs issued for the purpose of the execution of a sentence. The underlying idea is that requested persons have already had the benefit of access to a lawyer − and possibly legal aid − during the trial that led to the sentence concerned. In respect of in absentia trials, however, this will not always be the case.

As regards the condition under b), the wording "in so far as such aid is necessary to ensure effective access to justice" was literally copied from Art. 47 of the Charter. The condition is fulfilled "where the lawyer in the executing Member State cannot fulfil his or her tasks as regards the execution of a European arrest warrant effectively and efficiently without the assistance of a lawyer in the issuing Member State."55 This underlines and defines the margin of discretion of the Member States.

There is no merits test as regards legal aid in EAW proceedings (for both the lawyer in the executing and in the issuing State). Such merit is presumed to exist where an EAW has been issued. However, Member States may apply a means test (Art. 5(3)).

b) Costs relating to legal aid for the lawyer in the executing State

During the discussions in the Council, a curious question was raised: which State should bear the costs of legal aid for the lawyer in the executing State?

It was always assumed that the executing State should bear these costs, since Art. 30 of Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA states that "[e]xpenses incurred in the territory of the executing Member State for the execution of a [EAW] shall be borne by that Member State. All other expenses shall be borne by the issuing Member State." However, it was submitted that costs for legal aid should not be considered expenses for the execution of an EAW, as a result of which these costs should be borne by the issuing State.

The question was discussed in the Coordinating committee in the area of police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters (CATS),56 where it was confirmed that the executing State should bear the costs of legal aid for the lawyer in that State. Hence, the executing and issuing States have to bear the costs of legal aid for assistance by lawyers who have been appointed in their own States.

The fact that issuing States, as a result of the legal aid Directive, now "risk" possibly having to pay legal aid for a lawyer in the context of the execution of an EAW could incidentally be an incentive for them to abstain from using the EAW system for petty offences or trivial cases.

c) Summary of the eligibility provisions

The eligibility for legal aid, as regards both legal aid for suspects and accused persons in criminal proceedings as well as legal aid for requested persons in EAW proceedings, can be summarized as follows:

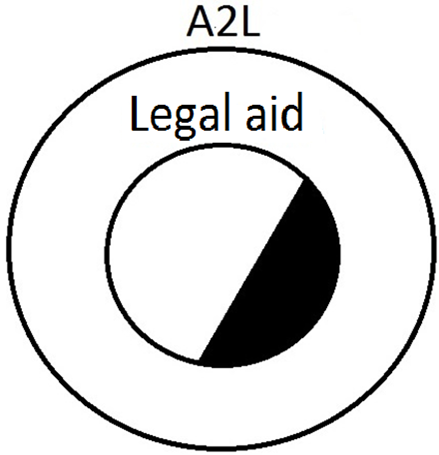

In order to be eligible for legal aid under the legal aid Directive, suspects, accused, and requested persons must first of all have the right of access to a lawyer under Directive 2013/48/EU ("A2L," outer circle). Moreover, suspects and accused persons may need to pass the means and/or merits test, and requested persons may need to pass the means test (inner circle). These tests leave considerable margins of discretion to the Member States. However, when suspects or accused persons are detained and when detention is at stake, the merits test is deemed to have been met, which is also always the case in EAW proceedings (section in black). In such situations, the persons concerned should be granted legal aid, unless it is determined through a means test that they have sufficient resources to pay for the assistance of a lawyer themselves.

3) Decisions on granting of legal aid

It is important to have good laws, but it is just as important that laws are applied properly. This holds even truer when a law, such as the Directive on legal aid, provides large margins of discretion.

For this reason, and inspired by the Commission recommendation, the European Parliament in its orientation vote proposed that decisions on whether or not to grant legal aid and decisions on the assignment of lawyers should be made promptly by an independent competent authority. Parliament also proposed providing that Member States should ensure that the responsible authorities make decisions diligently and that substantial guarantees against arbitrariness are in place.

Although the Member States could agree with the spirit of this proposal, they were reluctant to concede that decisions on legal aid should always be taken by an independent competent authority (such as an independent legal aid board), since decisions on legal aid are often taken by courts or judges, and sometimes also by the police or by prosecutors.

While the European Parliament could accept that decisions on legal aid are taken by courts or judges, which are also considered to be independent, it insisted that decisions on legal aid or the assignment of lawyers should not be taken by the police or by prosecutors dealing with the case at hand, since they could have an interest in not granting legal aid or assigning a particular lawyer.

As a compromise, it was agreed to refer in the operative part of the text to a "competent authority." It is now provided that decisions on whether or not to grant legal aid and on the assignment of lawyers should be made by a competent authority without undue delay. Member States should take appropriate measures to ensure that the competent authority makes its decisions diligently, respecting the rights of the defence (Art. 6(1)).

In the recitals, it is clarified that the competent authority should be an independent authority that is competent to take decisions regarding the granting of legal aid, e.g., a legal aid board or a court, including a judge sitting alone. However, in urgent situations only, the temporary involvement of the police and the prosecution should also be possible in so far as this is necessary to be able to grant legal aid in a timely manner.57

The possible involvement of the police and the prosecution in urgent situations seems fair, since the necessity is partly due to modifications in other parts of the text (e.g., the modified subject matter of Art. 4, no longer provisional legal aid but legal aid) and since the Directive requires Member States to grant legal aid at the latest before questioning or before an investigative or evidence-gathering act is carried out (Art. 4(5), see above).

4) Quality of legal aid services

Art. 7 constitutes yet another example of where the text has been modified because of proposals by the European Parliament. This article contains requirements regarding the effectiveness and quality of the legal aid system as well as regarding the quality of legal aid services.

Again, the European Parliament was clearly inspired by the Commission recommendation. The text as agreed provides that Member States should take necessary measures, including those with regard to funding in order to ensure that: (a) there is an effective legal aid system of an adequate quality; and (b) legal aid services − namely services provided by a lawyer who is funded by legal aid − are of a quality adequate to safeguard the fairness of the proceedings (Art. 7(1)).

This is clear and rather strong language. While it could be argued that many other provisions of the Directive leave a lot of margin and/or merely copy provisions of the Charter and the ECHR, it seems that Art. 6 and, even more, Art. 7 at least provide rules that have substantial practical and added value.

5) Various practical arrangements and remedies

The rapporteur of the European Parliament requested to keep the Directive short and simple, without any unnecessary details. This request was followed, and the Directive is rather short, with relatively few recitals (33 − the other procedural rights Directives often have twice as many). As a result, the Directive provides the legislative framework for the granting of legal aid in the Member States, but all practical and detailed arrangements are to be filled in by the Member States, as is also specified in the recitals.58 This concerns issues like clawback, which had been discussed intensively during the negotiations, but in respect of which the final text of the Directive remains silent. Hence, under the control of the Court of Justice of the EU, the Member States are free to decide whether their authorities may request beneficiaries of legal aid to pay such aid back (e.g. when a court or a judge finds that they were guilty of having committed a criminal offence).

As regards remedies, the Commission did not provide any provision in this regard. The Council and the European Parliament agreed to insert a standard clause, according to which Member States should ensure that suspects, accused persons, and requested persons have an effective remedy under national law in the event of a breach of their rights under the Directive (Art. 8).

IV. Conclusion

Directive 2013/48/EU provides rules on the right of access to a lawyer. The Directive sets out when suspects, accused, and requested persons have the opportunity to be assisted by a lawyer. However, when persons who have the right of access to lawyer lack financial resources, they might not be effectively assisted by a lawyer. It was therefore very important to adopt the Directive on legal aid, which complements the Directive on access to a lawyer (and the Directive on safeguards for children). It was fortunate that the Directive on legal aid could be adopted before the deadline for transposition of the Directive on access to a lawyer expired.59

For a long time, uncertainty existed as to whether a Directive on legal aid would see the light of day, since the subject matter was complicated, and positions within the Member States and between the institutions lay far apart from each other. A further element of uncertainty was the impact assessment that had been ordered by the European Parliament in the middle of the negotiations.

The Commission proposal for a Directive was not very ambitious, but the accompanying recommendation contained a lot of material that could beef the text up. The European Parliament effectively made use of this possibility. The form and content of the Directive as finally agreed are to a large extent influenced by proposals of the European Parliament, on the basis of the recommendation of the Commission. That text, in turn, was largely inspired by the Charter, ICCPR and, notably, by the ECHR (including the ECtHR’s case law). Therefore, various parts of the Directive resemble the latter. However, codification of these rules in a directive contributes added value in view of the binding nature of this legal instrument and the enforcements mechanisms under the TFEU. Staying close to the ECHR – to which all Member States are parties – was also key to ensuring that the text of the Directive could be accepted by a very large majority of Member States, from North to South and from East to West.

The text of Directive (EU) 2016/1919, which is rather lean, allows Member States sufficient flexibility to transpose the Directive into their national legal orders. Such transposition is to be carried out by Spring 2019. It is hoped that the Commission will actively follow the implementation process and that it will not refrain from starting infringement proceedings when Member States do not implement the Directive in a timely or correct manner.60 This will contribute to ensuring that the Directive has added value.

The Directive will most likely give rise to interpretative case law by the CJEU. Perhaps the Directive will also inspire the case law of the ECtHR, as has been the case with other procedural rights Directives in the past.61

(*) This article reflects solely the opinion of the author and not that of the institution for which he works.

Although it is provided that the catalogue of measures set forth in the Roadmap has a non-exhaustive nature, see recital 12 of the Resolution of the Council of 30 November 2009 on a Roadmap for strengthening procedural rights of suspected or accused persons in criminal proceedings, O.J. C 295, 4.12.2009, p. 1.↩︎

See the reference in the previous footnote.↩︎

The step-by-step approach was adopted after it had initially appeared to be impossible, in 2007, to reach agreement on a comprehensive text encompassing several procedural rights – see the never adopted proposal for a Framework Decision on certain procedural rights in criminal proceedings throughout the European Union (COM 2004/0328).↩︎

O.J. L 190, 18.7.2002, p. 1.↩︎

O.J. L 130, 1.5.2014, p. 1.↩︎

O.J. L 280, 26.10.2010, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras and L. De Matteis, "The Directive on the right to interpretation and translation in criminal proceedings", (2010) eucrim, 153.↩︎

O.J. L 142, 1.6.2012, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras, and L. De Matteis, "The Directive on the right to information", (2013) eucrim, 22.↩︎

O.J. L 294, 6.11.2013, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras, "The Directive on the right of access to a lawyer in criminal proceedings and in European arrest warrant proceedings", (2014) eucrim, 32.↩︎

O.J. L 65, 11.3.2016, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras and Anže Erbežnik, "The Directive on the presumption of innocence and the right to be present at trial", (2016) eucrim, 25.↩︎

O.J. L 132, 21.5.2016, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras, "The Directive on procedural safeguards for children who are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings", (2016) eucrim, 109.↩︎

In fact, in its proposal the Commission combined one aspect of measure C (legal advice, “C1”) with measure D, concerning communication with relatives, employers, and consular authorities.↩︎

As has been observed in the past, the Commission was free to design its proposal in this manner, since the Roadmap itself states that the order of the rights indicated therein is "indicative". More importantly, the Roadmap does not affect the basic right of initiative of the Commission: this institution can decide not only whether or not to present a proposal but also on the contents of its proposals. See Cras, op. cit. (n. 8), 32.↩︎

Explanatory memorandum to COM(2011) 326/3, point 1.↩︎

Belgium, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, United Kingdom.↩︎

Council doc. ST 14495/11, point IV.↩︎

Art. 12(2) of the Commission proposal [COM(2011) 326/3], as clarified in point 29 of the accompanying explanatory memorandum.↩︎

See Art. 11 of Directive 2013/48/EU.↩︎

Council doc. ST 10908/12.↩︎

Of course, if the Commission would not have presented a proposal for a Directive on legal aid, a quarter of the Member States could have presented a Member States' initiative on this issue, in accordance with Art. 76 under b) TFEU. This was not a very attractive perspective, however, in view of the sensitive nature of the subject matter.↩︎

COM(2013) 824.↩︎

The two others proposals were COM(2013) 821 on the presumption of innocence (which later became Directive (EU) 2016/343) and COM(2013) 822/2 on procedural safeguards for suspected or accused children (which later became Directive (EU) 2016/800).↩︎

Commission Recommendation of 27 November 2013 on the right to legal aid for suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings, O.J. C 378, 24.12.2013, p. 11.↩︎

The Council’s general approach reflects its vision on the Commission proposal and is, in practice, the starting point for its negotiations with the European Parliament in the context of the ordinary legislative procedure of Art. 294 TFEU.↩︎

Council doc. ST 6603/15.↩︎

Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Lithuania.↩︎

Council doc. ST 7166/15 ADD 1.↩︎

The official term is "Legislative Resolution". Since the (old) term "orientation vote" was commonly used in the negotiations, it is also used in this text.↩︎

Orientation vote adopted on 6 May 2015, EP doc. A8-0165/2015.↩︎

Council doc. ST 12845/15.↩︎

Council doc. ST 13302/15.↩︎

The European Parliament’s Directorate for Impact Assessment and European Added Value.↩︎

For the outcome of the bilateral meetings, see Council doc. ST 5556/16, point B.↩︎

Council doc. ST 8047/16, p. 4.↩︎

Council doc. ST 8047/16, p. 6.↩︎

In the Dutch political landscape, the ideas of the political party of Minister Van der Steur (VVD) have often been diametrically opposed to the ideas of the political party of rapporteur De Jong (SP). It was nice to see that in "Brussels" they helped each other to achieve their (common) goals.↩︎

Council doc. ST 10665/16.↩︎

In the end, all Member States except Poland supported the Directive. When the Council formally agreed to the Directive on 13 October 2016, Poland presented the following declaration: "Poland does not support the so-called “compromise” presented for adoption at the Council meeting on 13 October 2016. We feel that an appropriate compromise taking due account of the interests of both Member States and suspected and accused persons was expressed in the general approach text adopted by the Council in February 2015. The present draft is in fact an unwarranted concession to the European Parliament and made by it without regard to the overall impact of this document and its internal consistency. Poland cannot in particular support the extension of the draft directive beyond its intended scope of temporary legal aid, the exclusion of specific provisions relating to less serious offences and the obligation to provide legal aid in the state issuing an EAW." (Council doc. ST 12835/16 ADD 1).↩︎

Recital 1.↩︎

See Arts. 6 and 18 of Directive (EU) 2016/800. On this issue, see Cras, op. cit. (n. 10), 114.↩︎

See the explanatory memorandum to the Commission proposal, in particular point 10.↩︎

See, e.g., the Council’s general approach (Council doc. ST 6603/15), recital 12b.↩︎

See, e.g., ECtHR, 13 October 2009, Dayanan v. Turkey, Appl. 7377/03, para. 31.↩︎

See Art. 3(4), second indent, and recital 28 of Directive 2013/48/EU.↩︎

See Art. 3(3)(c) and recital 26 of Directive 2013/48/EU.↩︎

See above II.3 and note 22.↩︎

ECtHR, 25 April 1983, Pakelli v. Germany, Appl. no. 8398/78, para. 34.↩︎

ECtHR, 24 May 1991, Quaranta v. Switzerland, Appl. no. 12744/87, paras. 32-34.↩︎

Recital 13.↩︎

This provision is almost a literal duplicate of Art. 13 of Directive 2013/48/EU.↩︎

See Art. 6(6) of Directive (EU) 2016/800.↩︎

Compare ECtHR, 10 June 1996, Benham v. UK, Appl. no. 19380/92, para. 61: "The Court agrees with the Commission that where deprivation of liberty is at stake, the interests of justice in principle call for legal representation (…). In this case, Mr Benham faced a maximum term of three months' imprisonment."↩︎

Art. 2(1) of Directive 2013/48/EU.↩︎

Recital 19.↩︎

Art. 10 of Directive 2013/48/EU.↩︎

Recital 21.↩︎

Council doc. ST 14302/14.↩︎

Recital 24.↩︎

Recital 18.↩︎

The deadline for transposition of Directive 2013/48/EU expired on 27 November 2016, one month after the Directive on legal aid had been adopted.↩︎

See, as regards infringement proceedings, the recent Communication from the Commission, "EU law: Better results through better application", O.J. C 18, 19.1.2017, p. 10.↩︎

See, in relation to Directive 2013/48/EU: ECtHR, 9 April 2015, A.T. v. Luxembourg, Appl. no. 30460/13, paras. 38 and 87.↩︎