The Directive on Procedural Safeguards for Children who Are Suspects or Accused Persons in Criminal Proceedings Genesis and Descriptive Comments Relating to Selected Articles

Abstract

The article explains the genesis and content of Directive (EU) 2016/800 on procedural safeguards for children who are suspects or accused in criminal proceedings, the fifth measure of the Roadmap on procedural rights. Cras outlines the legislative negotiations and comments on selected provisions: scope and definition of children, the right to information, mandatory assistance by a lawyer with legal aid, individual assessment, medical examination, audio-visual recording of questioning, safeguards during deprivation of liberty, protection of privacy, and participation in court hearings. The Directive, inspired by international standards such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, introduces binding EU minimum rules and strengthens child-friendly justice, though compromises mean that some protections remain limited.

I. Introduction

On 11 May 2016, the European Parliament and the Council adopted Directive (EU) 2016/800 on procedural safeguards for children who are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings.1 The Directive is the fifth legislative measure that has been brought to pass since the adoption of the Council’s Roadmap in 2009. This article describes the genesis of the Directive and provides descriptive comments relating to selected articles.

II. Genesis of the Directive

1. Background: Roadmap

In November 2009, the Council (Justice and Home Affairs) adopted the Roadmap for strengthening procedural rights of suspected or accused persons in criminal proceedings.2 The Roadmap provides a step-by-step approach – one measure at a time – towards establishing a full EU catalogue of procedural rights for suspects and accused persons in criminal proceedings. The Roadmap invites the Commission to submit proposals for legislative measures on five rights (A–E), which the Council pledged to deal with as matters of priority.

Subsequently to its adoption, the Roadmap has been gradually rolled-out. Until the beginning of May 2016, four measures had been adopted: Directive 2010/64/EU on the right to interpretation and translation,3 Directive 2012/13/EU on the right to information,4 Directive 2013/48/EU on the right of access to a lawyer,5 and Directive (EU) 2016/343 on the presumption of innocence.6

2. The Commission proposal

In November 2013, the Commission submitted its proposal for a Directive on procedural safeguards for children who are suspected or accused in criminal proceedings. The proposal clearly related to measure E of the Roadmap, concerning "special safeguards for suspected or accused persons who are vulnerable". However, since it appeared difficult to find a common definition of "vulnerable persons", and in view of considerations linked to the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality, the Commission decided to restrict its proposal to one category of vulnerable persons that could easily be defined, namely suspected or accused children.7

The proposal defines children as persons below the age of 18 years. Drawing inspiration from the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), the Commission in its proposal stated that, due to their age and lack of maturity, special measures need to be taken to ensure that children can effectively participate in criminal proceedings and benefit from their fair trial rights to the same extent as other suspects or accused persons.8 Because of its restricted scope, the (proposal for a) Directive was regularly referred to as "measure E-" (E-minus); in the corridors, one also used to refer to "the children Directive".

The nature of the proposal was different from the nature of the other measures of the Roadmap. Whereas the other measures set rules regarding one or more specific procedural rights that apply to all suspects and accused persons, including suspected or accused children, this proposal aimed at setting (more protective) rules regarding various procedural rights benefitting the specific category of suspected or accused children. For this reason, the proposal also formed part of the EU Agenda for the rights of the child, which had been presented by the Commission in 2011.9

As regards adult vulnerable persons, on the same day it presented the proposal on "children", the Commission presented a Recommendation on procedural safeguards for vulnerable persons suspected or accused in criminal proceedings and vulnerable persons subject to European Arrest Warrant proceedings.10 This Recommendation is a non-binding act, which aims at encouraging Member States to strengthen the procedural rights of all vulnerable suspects or accused persons. It was adopted unilaterally by the Commission and hence constitutes solely the point of view of this institution. The future will tell what the influence of this "soft law" measure will be.

3. Discussions in the Council

The proposal for “the children Directive” was generally welcomed by the major stakeholders. In the Council, almost all Member States expressed positive reactions, subject to certain modifications being made to the text.11 This was one of the reasons why the Greek Presidency, which was in charge during the first semester of 2014, decided to start discussions on this proposal (and leave the discussions on the proposals on the presumption of innocence12 and on legal aid,13 which had been simultaneously presented by the Commission, to subsequent Presidencies).

The proposal was discussed in several meetings of the Working Party on Substantive Criminal Law (Droipen). In the margins of one such meeting, representatives of the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) presented the results of research demonstrating why children should receive special protection in criminal proceedings. Several Member States pointed out, however, that the research carried out by the FRA related to the situation of children who are victims, and that this situation should be distinguished from the situation in which children are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings.14

The Council reached a general approach on the text in June 2014.15 Criticism was expressed from various sides on this general approach, as the standards of protection it set seemed low.16 However, as has been observed in respect of other Roadmap measures, in the context of the co-decision procedure the Council has become used to establishing modest standards of protection in its general approach, so as to leave some margin for the negotiations with the European Parliament concerning the final text.

Ireland and the United Kingdom decided not to participate in the adoption of the Directive, in application of Protocol N°21 to the Lisbon Treaty. In addition, Denmark did not participate, in accordance with Protocol N°22 to the Lisbon Treaty.

4. Negotiations with the European Parliament

In the European Parliament, the discussions on the proposal began only after the parliamentary elections had taken place in May 2014. The file was attributed to the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE), and Ms Caterina Chinnici (Italy, Socialists) was appointed first responsible member ("rapporteur"). Having worked for decades in Italy in the field of juvenile justice, Ms Chinnici was particularly well qualified to carry out this task.

In February 2015, the LIBE Committee adopted its orientation vote on the proposal for a Directive. Subsequently, negotiations started between the European Parliament and the Council,17 with the assistance of the Commission as "honest broker". In the initial months, the Council was represented by the Latvian Presidency and, as from 1 July 2015, by the Luxembourg Presidency.

The negotiations took place partially in trilogues (in the presence of i.a. rapporteur Chinnici and the shadow rapporteurs or their assistants) and partially in technical meetings (with experts on desk/working level representing the three involved institutions). The technical meetings, which were particularly intense, had the aim of preparing the trilogues, by mutually exchanging points of view and their underlying reasons, and by drafting possible compromise texts for discussion/confirmation in the trilogues.

The negotiations first concentrated on the less controversial issues, such as the right to information, the individual assessment, and the medical examination. The most difficult issue, concerning the right of access to a lawyer, was left to the end, since it was felt that this would be the hardest nut to crack. Some feared, understandably, that this might entail some risks: one wanted to be sure that the provisions on the right of access to a lawyer would be fully agreeable before showing flexibility on the other issues. In order to make progress, however, it was necessary to negotiate and agree, at least provisionally, one article after the other. And it was understood, in any event, that "nothing is agreed until everything is agreed".

During the last weeks, the negotiations were particularly hectic. The aim was to complete the file before Christmas, but there was still a lot of work to be done. In the end, provisional agreement was reached at the 9th trilogue, which took place on 15 December 2015 in Strasbourg. The next day in Brussels, COREPER confirmed the agreement and the habitual letter was sent to the European Parliament.18

After the usual legal-linguistic examination of the text, the Directive was finally adopted on 11 May 2016. It was published in the Official Journal of 21 May 2016. The Member States have to transpose the Directive into their legal orders by 11 June 2019.

III. Comments Relating to Some Specific Elements of the Directive

1. General observations

The Directive sets minimum rules on several procedural rights for children. In respect of some issues, similar rights exist in other procedural rights directives that are applicable to all suspects and accused persons. Where this is the case, the rights of this Directive, which aims at setting higher standards of protection, take precedence: the Directive is a lex specialis.

The higher standards of this Directive are justified because children are considered to be vulnerable. In the course of the discussions in the Council, however, several Member States pointed out that one should not have a too idealistic view of "children" in the context of criminal proceedings. While these may concern children who are accidentally confronted with the police, they may also concern juveniles aged 16 or 17 years who commit criminal offences on a regular basis.

It would probably be appropriate to call the instrument "the Directive on the child’s best interests". In fact, many times in the text it is said that action of Member States should be compatible with the child’s best interests, or that Member States should take these interests into account. These references could probably be considered superfluous, since Art. 24(2) of the Charter already provides that "In all actions relating to children (…) the child’s best interests must always be a primary consideration." On many points, however, explicit references to the child’s best interests proved to be an adequate solution to reach a compromise between the two co-legislators.

Ultimately, it should be noted that the Directive has drawn substantive inspiration from international standards, such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) and the Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child-friendly justice (2010).

Descriptive comments relating to some selected articles of the Directive are set out below. It is by no means an exhaustive overview of the Directive.

2. Scope (Arts. 2 and 3)

a) Personal scope

The Directive applies to children, which, as indicated above, means persons below the age of 18 years. This is in line with instruments of international law.19

Upon request of the European Parliament, it has been clarified that the age of the child should be determined on the basis of the child’s own statements, civil status checks, documentary research, other evidence, and – only if evidence is unavailable or inconclusive – on the basis of a medical examination. Medical examination is only a measure of last resort and has to be carried out in strict compliance with the child’s rights, physical integrity, and human dignity. In case of doubt, there is a presumption of childhood.20

In its proposal, the Commission had inserted a provision according to which the personal scope of the Directive would be extended to suspects or accused persons who have become of age but who were children when the criminal proceedings started. In the Council, several Member States fiercely opposed this provision. According to these Member States, one either is a child or one is not: hence, the Directive should not apply to children that become adults. The Member States concerned indicated that ex-children themselves might not want the Directive to still apply to them after they have become of age. Reference was made in this respect to the provisions according to which a holder of parental responsibility should be involved in the criminal proceedings. In view of this, the Council in its general approach transformed the obligatory provision of the Commission proposal into an optional "may"-provision.

During the negotiations with the European Parliament, a compromise was reached on an obligatory provision to extend the application of the Directive to persons who have become of age but who were children when they became subject to the proceedings. However, the following important precisions were introduced:

The extension does not apply to provisions21 that refer to the involvement of the holder of parental responsibility;

The application of the Directive should be extended only when this is "appropriate", based on a case-by-case assessment in the light of all the circumstances of the case, including the maturity and vulnerability of the person concerned;

Continued application may also concern certain provisions of the Directive only; and

The Member States may put a final "cap" on the application of the Directive by deciding that the Directive should in any event no longer apply in respect of persons who have reached the age of 21.

b) Temporal Scope

As regards the starting point of the application of the Directive, it is recalled that the first three directives that were adopted in the field of procedural rights22, all provide that these instruments apply from the moment that the persons concerned have been made aware – by official notification or otherwise – of the fact that they are suspected or accused of having committed a criminal offence.

The Commission had proposed, however, that this Directive should apply earlier, namely when children "become suspected or accused of having committed an offence". According to the Commission, certain elements of the Directive, notably the right to the protection of privacy, should apply even before children have been made aware that they are suspects or accused persons.

While the Council was initially reluctant to accept such an earlier kick-off point, it was later willing to do so. This was due to the fact that a lot of articles of the Directive were linked to a later point in time in the proceedings anyway (e.g. deprivation of liberty, detention) and, perhaps more importantly, because a precedent had been created in the meantime: in the Directive on the presumption of innocence, which was agreed upon in October 2015, the Council had also accepted an earlier kick-off moment.

In the final text of the Directive on children, the same formula as that used in the Directive on the presumption of innocence was chosen. The Directive hence applies "to children who are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings". It is to be noted, however, that because of this modified kick-off, point, the text of Art. 4 on the provision of information was revised, since information on procedural rights can obviously only be given once a child has been made aware that he is a suspect or accused person.

As regards the end point of the application, the question was raised as to whether the Directive could and should apply to the execution phase (after a final sentence has been handed down). This would notably be relevant with regard to the provisions concerning the detention of a child. Various Member States considered the reference in Art. 82(2)(b) TFEU to "the rights of individuals in criminal procedure" to mean that there would be no power to adopt legislation that would be applicable to the execution phase, since the criminal proceedings would already have been completed.23 The Commission strongly contested this. These discussions were important, also in the light of possible future legislation (e.g. regarding detention conditions).

Although legal advice was sought, it was generally considered that the question raised was of a political nature. In the final compromise, the European Parliament accepted the position of the Council. It was therefore agreed that the Directive, staying in line with the previous directives on procedural rights, would apply until the decision on the final determination of the question whether the suspect or accused person has committed a criminal offence has become "definitive". The Directive thus does not apply to the execution phase.

3. Right to information (Arts. 4 and 5)

It is important to award procedural rights to children, but it is equally important to inform children that they have these rights, so that they can exercise them.

The Commission proposed that children should be informed "promptly" of their rights under this Directive.24 The Council, however, maintained that providing children with all the information on their rights at the beginning of the proceedings would be disproportionate, partially irrelevant (e.g. if it relates to rights that would probably never become relevant for the child concerned, such as rights when in pre-trial detention), and not in the interest of the child. The Council therefore suggested that information should be provided to children "where and when these rights apply".

The European Parliament went along the line of the Commission, but it had some additional requests: referring to case law of the ECtHR,25 it demanded i.a. that the child should also be informed "about general aspects of the conduct of the proceedings". The Council objected to this request, observing i.a. that providing such information is the responsibility of the lawyer, that it might prejudice the proceedings, and that it would constitute a substantial extra burden for the competent authorities.

The text as finally agreed makes a distinction between the different stages of the proceedings26 and sets out which information children should receive during each stage. This is accompanied by a recording obligation,27 which had been suggested by the Commission in order to ensure that the information is actually provided to children. This solution seems to make sense and provides added value. The text also foresees that the children be informed about the general aspects of the conduct of the proceedings but, in the light of the objections presented by the Council, it is explained in the recitals that this should include, in particular, "a brief explanation about the next procedural steps in the proceedings in so far as this is possible in the light of the interest of the criminal proceedings, and about the role of the authorities involved. The information to be given should depend on the circumstances of the case."28

The Directive further sets rules on the information that should be provided to the holder of parental responsibility or, where applicable, "another appropriate adult". That person is then in a position to assist the child concerned, e.g. by appointing a lawyer. It is to be noted that the holder of parental responsibility must also be informed because he/she is legally responsible for the child and can be held civilly liable. A definition of the holder of parental responsibility (based on family law29) was included in the Directive.30

4. Assistance by a lawyer and legal aid (Arts. 6 and 18)

Art. 6 of the Commission proposal on "mandatory assistance" by a lawyer was probably the most controversial article of the entire Directive. This is understandable, since the Commission had proposed that all children in criminal proceedings who have the right of access to a lawyer in accordance with Directive 2013/48/EU ("A2L Directive") should be assisted by a lawyer. Legal aid should be provided by the Member States to fund the costs of such a lawyer. The Commission proposal could therefore have substantial financial consequences for the Member States.31

The Council in its general approach presented a counter-proposal. It made a clear distinction between the "right of access to a lawyer" and "assistance by a lawyer". In Art. 6 it recalled that children have the right of access to a lawyer in accordance with the A2L Directive. As observed earlier, this right provides the opportunity for suspects and accused persons, including children, to benefit from legal support and representation by a lawyer.32 To this effect, the State should not prevent the lawyer from being present at specific moments during the criminal proceedings. However, this opportunity does not mean that a lawyer will indeed be present, since the person may not have the means to pay a lawyer himself and there may be no legal aid available under the system of the Member State concerned.

The Council suggested inserting provisions regarding assistance by a lawyer in a new Art. 6a. Such assistance means that the presence of a lawyer is, in principle,33 guaranteed: if the child, or the holder of parental responsibility, has not arranged a lawyer himself, the State should arrange a lawyer. Moreover, the State should provide legal aid if the child, or the holder of parental responsibility, does not have the means to pay the lawyer himself.

The Council in its general approach suggested that assistance should be available for children who have the right of access to a lawyer in accordance with the A2L Directive and who either are questioned by the police or another law authority (unless providing assistance by a lawyer would not be proportionate) or are deprived of liberty (unless the deprivation of liberty is only to last for a short period of time).

Both the European Parliament and the Commission had misgivings on the Council’s text. The Commission observed i.a. that a "short period of time" was a vague notion, which could easily be applied in an undesired manner. The European Parliament had fundamental objections to the link with the A2L Directive, considering it to be a "black hole" full of exceptions and derogations.34 The European Parliament therefore requested drafting Art. 6 of the children Directive as a "stand alone" provision, without making reference to the A2L Directive.

In view of this latter request of Parliament, Art. 6 was considerably revised. Large parts of the A2L Directive were copied and transferred to that article, modifying "access to a lawyer" by "assistance by a lawyer". In the light of the objections of the European Parliament to the derogations of the A2L Directive, the Council accepted that the derogation of Art. 3(5) of said Directive concerning "geographical remoteness" would not be transferred. The Council insisted, however, on transferring the derogation of Art. 3(6) of the A2L Directive regarding life and limb and substantial jeopardy to criminal proceedings (although the text was made more stringent with a reference to "serious criminal offence").

The most difficult part in reaching a compromise on the text as thus revised was finding a proper balance regarding the situations in which assistance should be provided. In this context, the European Parliament presented a "wish list",35 and the point was discussed at various (multi-lateral) meetings in the Council, sometimes in the presence of the Commission. During these meetings, a substantial group of Member States insisted that, for various minor and less serious offences (e.g. driving a bike without helmet, shoplifting, causing relatively minor damage to the property of a third person, and various public order offences), it would not be necessary or even useful to provide the child with assistance by a lawyer.

The attempt was made to find a solution by distinguishing between situations in which children are not deprived of liberty ("at large"), and situations in which children are deprived of liberty.36 However, legal advice was provided to the negotiators that the criterion of "deprivation of liberty" should not be used, since it did not figure in the ECHR and in the case law of the ECtHR.

In the end, with a view to reaching a compromise, it was agreed to insert a horizontal proportionality clause in the text and to install some safety nets. According to the proportionality clause, Member States may derogate from the obligation to provide assistance by a lawyer where this would not be proportionate in the light of the circumstances of the case, taking into account the seriousness of the alleged criminal offence, the complexity of the case, and the measures that could be taken in respect of such an offence.37 In order to counter-balance the flexibility that this provision provides to Member States, two additions were made:

The right to a fair trial should be complied with, implying that the application of this provision should be in conformity with the ECHR and the case law of the ECtHR;

The child’s best interests should always be a primary consideration.

As regards the safety nets, the European Parliament preferred to state that no entry in criminal records would be made unless the child had been assisted by a lawyer. This appeared very difficult, however, in view of the substantial differences between the criminal records of the Member States. Therefore, two other safety-nets were installed:

The first one is that children should be assisted by a lawyer, in any event, when they are brought before a competent court or judge in order to decide on detention at any stage of the proceedings, and during detention. In the light of the temporal scope of the Directive, such detention means pre-trial detention (including detention during the trial, but excluding detention that is the result of the execution of a final sentence).

The second safety net is that deprivation of liberty should not be imposed as a criminal sentence unless the child has been assisted by a lawyer in such a way as to allow the child to exercise the rights of the defence effectively and, in any event, during the trial hearings before a court.

In accordance with Art. 6 as thus agreed, Member States should ensure that children are assisted by a lawyer.38 In our view, children cannot waive being assisted by a lawyer: no provision on waiver is foreseen, and the assistance by a lawyer is an obligation for Member States, not a right for children. Member States should arrange for the child to be assisted by a lawyer where the child or the holder of parental responsibility has not arranged such assistance. Member States should also provide legal aid where this is necessary to ensure that the child is effectively assisted by a lawyer.39 Indeed, following Art. 18, Member States should ensure that national law in relation to legal aid guarantees the effective exercise of the right to be assisted by a lawyer pursuant to Art. 6.

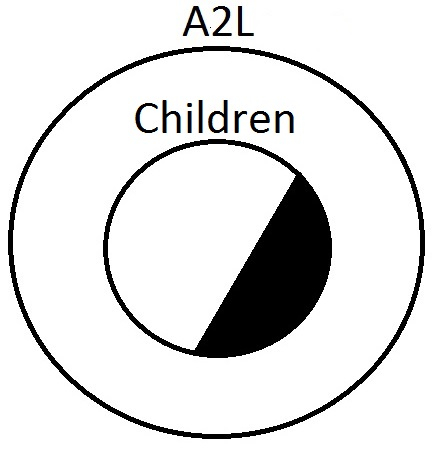

Art. 6 may be summarized using the following figure, which also explains the interplay of “the children Directive” with the “access to a lawyer Directive” (A2L Directive):

Children have the right of access to a lawyer in accordance with the A2L Directive: as explained above, it provides the opportunity for children to have a lawyer. Children should be assisted by a lawyer in accordance with the children Directive: it provides a guarantee to children that they will have a lawyer. Assistance by a lawyer under the children Directive presupposes that the child has the right of access to a lawyer under the A2L Directive;40 therefore, the circle of the children Directive falls within that of the A2L Directive. In the circle of the children Directive, the black part represents the safety nets: in these situations, assistance should be provided in any event. The white part depends on the application of the proportionality test by the Member States.

5. Individual assessment (Art. 7)

Children are individuals who may have specific needs. Art. 7 therefore provides that children who are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings should be individually assessed in order to identify their specific needs in terms of protection, education, training, and social integration.

The negotiations regarding this particular article went relatively smoothly. The biggest problem concerned the moment at which the individual assessment should take place. While the Council agreed with the other two institutions that the individual assessment should take place as early as possible, it remarked that it could take some time to make a sound and meaningful individual assessment.

It was agreed, therefore, that the individual assessment should take place at the earliest appropriate stage of the proceedings and in due time so that the information deriving therefrom can be taken into account by the prosecutor, judge, or another competent authority before presentation of the indictment for the purpose of the trial. It is possible, however, to present an indictment in the absence of an individual assessment, provided that this is in the child’s best interest. This could be the case, for example, when a child is in pre-trial detention and waiting for the individual assessment to become available would unnecessarily risk prolonging such detention.41 In any event, the individual assessment should be available at the beginning of the trial hearings before a court.

As a result of requests by the European Parliament, Art. 7 was made more detailed, e.g. as regards the elements that should be taken into account in the individual assessment42 and as regards the purposes for which the information deriving from an individual assessment should be taken into account.43 As a result of another request by the European Parliament and in view of international standards,44 it was also provided that the individual assessment should be carried out by qualified personnel, following, as far as possible, a multidisciplinary approach.45

Art. 7 concerning the right to an individual assessment may prove to be one of the most important articles of the Directive, as it will allow for detecting when children need particular help and support − which is then hopefully addressed. As Fair Trials and CRAE have rightly observed, individual assessments are a crucial step in determining which adaptations to the proceedings are required in order to ensure that the child in question can participate effectively and to identify other specific needs of the child that must be met in order to keep the child safe and protect the child from harm. When a child is in conflict with the law, this is a strong indicator that the child is likely to be in need of support and protection from the authorities, e.g. because the child has experienced neglect, abuse, and/or bereavement in the past.46

6. Medical examination (Art. 8)

Art. 8 provides the right to a medical examination for children who are deprived of liberty. Such examination aims at assessing, in particular, the general mental and physical condition of the child. The results of the medical examination must be taken into account when determining the capacity of the child to be subjected to questioning, other investigative or evidence-gathering acts, or any measures taken or envisaged against the child.

The text that the co-legislators finally agreed upon is very close to the text that was proposed by the Commission. During the negotiations, however, the European Parliament requested substantially enlarging the scope of the article, by providing the right to a medical examination not only for children who are deprived of liberty but also "where the proceedings so require, or where it is in the best interests of the child". Moreover, the European Parliament requested extending the right so that it would encompass "medical care", i.a. "to improve the health and well-being of the child".

The Council could understand the concerns of the European Parliament for the health and well-being of children, but it could not accept the requests concerned. Providing the right to a medical examination to basically all children in criminal proceedings was considered to be disproportionate. Only when the State has deprived a child of his liberty would it be reasonable to require the State to take special care by carrying out a medical examination.

As regards the request to extend the right to medical care, the Council observed that this would de facto turn the Directive into a medical insurance: therefore this request was also not considered to be proportionate. Moreover, the Council felt that accepting the request would be in conflict with the legal base of Art. 82(2) TFEU. Of course, in case of urgency, medical assistance should be provided to a child. The Council was willing, therefore, to add a reference to that effect, also in view of Art. 4(2)(c) of Directive 2012/13/EU on the right to information. After negotiations, it was agreed to add the following: "Where required, medical assistance shall be provided."47

7. Audio-visual recording (Art. 9)

Children are vulnerable and they may therefore be less able than adults to face questioning by the police or other law enforcement authorities. According to the Commission, there is also a risk that the procedural rights and dignity of children may not be respected during questioning.48

In this light, the Commission proposed that the questioning of children be audio-visually recorded. Such recording could provide protection to children, e.g. because they could then demonstrate that they have been ill-treated by the questioning authority or that their procedural rights have been infringed upon. The recording could also afford protection to the police and other law enforcement authorities in that they could demonstrate that they treated the children fairly during questioning and that they respected their procedural rights.

In the Council, Member States observed that audio-visual recording of the questioning of children did not always have positive effects. It was observed that children could consider the audio-visual recording to be intimidating and that, as a consequence, they would not dare to speak anymore.49 This being, most Member States nevertheless assumed that audio-visual recording of the questioning of children could be positive. In this light, two main issues were raised: in which situations should there be an obligation to make an audio-visual recording and how does it tie in to the presence of a lawyer?

The Council fiercely opposed a categorical obligation to make audio-visual recordings. According to the Council, when children are not deprived of liberty (at large), there should be a possibility to make an audio-visual recording of questioning, whereas when children are deprived of liberty, there should only be an obligation to make such a recording if it is proportionate to do so. The example was given of a child who is brought to a police station after having been apprehended for a less serious offence, e.g. shoplifting of goods of minor value. If the police would like to pose some questions to the child in this situation, an audio-visual recording should not always be required.

The Council noted that the European Parliament sometimes seemed to have a certain mistrust in the handling of criminal proceedings by the competent authorities of the Member States. It considered that making an audio-visual recording during questioning of children by a judicial authority, e.g. during the trial, would be excessive in any event, since one should be able to assume that such questioning be handled correctly. The Council also suggested making a link to the presence of a lawyer. Member States should be able not to proceed with an audio-visual recording if the questioning takes place in the presence of a lawyer, since that already affords protection to the child.

The Commission and the European Parliament contested this latter argument, since the function of audio-visual recording and of assistance by a lawyer are different: while the audio-visual recording allows for checking whether the police or other law enforcement authorities handle the questioning in a correct manner, assistance by a lawyer aims at providing the child with the necessary legal support.

In the end, a compromise was found by way of an open formulation: questioning of children by police or other law enforcement authorities during the criminal proceedings should be audio-visually recorded when it is proportionate in the circumstances of the case, "taking into account, inter alia, whether a lawyer is present or not and whether the child is deprived of liberty or not". It was further added, as in other text passages, that the child’s best interests should always be a primary consideration. As an extra safety measure, it was agreed that when an audio-visual recording is not made, questioning should be recorded in another appropriate manner, e.g. by written minutes that are duly verified.

8. Deprivation of liberty (Arts. 10-12)

When children are deprived of liberty, they are in a particularly vulnerable position. Deprivation of liberty, in particular longer periods of deprivation of liberty when in pre-trial detention, can prejudice the physical, mental, and social development of children, and lead to difficulties as regards their reintegration into society.

The Directive therefore provides special safeguards for children when they are deprived of liberty. The problem in the negotiations was that the concept of deprivation of liberty is very broad. Efforts were made to provide a definition of this concept, but this appeared to be very difficult. Deprivation of liberty includes, in any event, situations in which children are apprehended/arrested, put in police custody, and kept in pre-trial detention.

During the negotiations, the Council insisted on making the rights foreseen in this article "tailor-made" to the various situations of deprivation of liberty. For example, the Council stressed that the obligation, which was set out in the Commission proposal, according to which Member States should take appropriate measures concerning education and training of the child during deprivation of liberty, was formulated too broadly. Only when longer periods of deprivation of liberty are involved, such as when the child is in pre-trial detention, would it be necessary to take care of this.

Art. 10 as agreed, states that deprivation of liberty of children should be limited to the shortest appropriate period of time and that deprivation of liberty, in particular detention, should only be imposed on children as a measure of last resort. This is in line with international standards.50 To avoid doubt, it is pointed out that this requirement is without prejudice to the possibility for police officers or other law enforcement authorities to apprehend a child in situations if it seems, prima facie, necessary to do so, such as in flagrante delicto or immediately after a criminal offence has been committed.51

Most of the remaining provisons of Arts. 10-12 apply in particular to detention, which again, in line with the scope of the Directive, means pre-trial detention. A decision to this effect is normally taken by a judge or a court. In the Directive it is provided that

Any detention should be based on a reasoned decision;

Detention of children should be subject to periodic review;

Recourse should be had, where possible, to measures alternative to detention;52 and

Appropriate measures should be taken relating i.a. to health, education, family life, access to programmes, and respect for freedom of religion or belief.53

Provisions were also agreed upon regarding the separation of children and adults when in detention. In line with international standards,54 detained children should be held separately from adults, unless it is considered to be in the child’s best interests not to do so. Special rules apply when a detained child turns 18 and regarding the detention of children together with young adults (it is recommended that they be persons up to and including 24 years55).

Following a request from the European Parliament, a provision on separation of children and adults when in police custody was also agreed upon: here, the Member States insisted on allowing a derogation when, in exceptional circumstances, it is not possible in practice to ensure such separation. This could be the case e.g. when, in connection with a football match, a large number of hooligans are arrested and there is not enough space in the local police cells to organise the separation of children and adults. In such a situation, however, particular vigilance should be required on the part of the competent authorities in order to protect the physical integrity and well-being of the children.56

Lastly, it is provided that the Member States should endeavour to ensure that children who are deprived of liberty meet with the holder of parental responsibility as soon as possible, if such a meeting is compatible with investigative and operational requirements. The provision has been formulated in a rather soft way, because the Member States had substantial concerns that a firm obligation to organise meetings between the holder of parental responsibility and the child who is deprived of liberty could, in certain cases, substantially complicate the criminal proceedings, in particular when these proceedings have just started (when a child is in pre-trial detention, it is much less of a problem).

9. Protection of privacy (Art. 14)

The protection of the privacy of children who are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings is very important. The necessity of such protection is also recognised in international standards.57 Involvement in criminal proceedings risks stigmatising children and may have − even more than for adult suspects and accused persons − a detrimental impact on their chances for (re-)integration into society and on their future professional and social life. The protection of the privacy of children involved in criminal proceedings is a critical component of youth rehabilitation.58

During the negotiations on the Directive, two main issues emerged regarding the protection of the privacy of children. The first issue concerned the question of whether such protection requires that criminal proceedings involving children should, as a general rule, be conducted in the absence of the public ("in camera"). The Commission and the European Parliament felt that this should be the case.

The Council, however, objected. While recognising the need to protect the privacy of children, it was observed that transparent and open justice is also a fundamental element of the rule of law. It referred in this context to Art. 6(1) ECHR, according to which everyone against whom a criminal charge is brought is entitled to a fair and public hearing. In its general approach, the Council therefore stated that the Member States should attempt to strike a balance by taking account of the best interests of children, on the one hand (which could e.g. be achieved by setting as a principle that trials against children be organised in the absence of the public) and of the general principle of a public hearing, on the other hand.59

As a compromise, it was agreed to provide in Art. 14 that the privacy of children during criminal proceedings should be protected and that, to this end, Member States should either provide that court hearings involving children are usually held in the absence of the public or allow courts or judges to decide whether to hold such hearings in the absence of the public. Hence, it should at least be possible in all the 25 Member States to conduct criminal proceedings involving children in the absence of the public.

The second issue related to the proposed obligation for Member States not to publicly disseminate information that could lead to the identification of a child. According to the Commission proposal, the authorities should, in particular, refrain from divulging the names and images of suspected or accused children and their family members.

The Council agreed, in principle, but stated that such an obligation should not prevent the competent authorities from publicly disseminating information that could lead to the identification of a child if this is strictly necessary in the interest of the criminal proceedings. One could think of criminal activity, such as robbery or sexual assault, which has been committed by persons that are apparently under 18. By publicising a photo or a video showing the (alleged) perpetrators, the police could ask the public for help in obtaining the identity of these persons.

During the negotiations, therefore, the Council suggested inserting two derogations, one for life and limb and one for the interest of the criminal proceedings.60 Upon the request of the Nordic countries, which have strict rules regarding transparency, the Council also suggested adding that Member States could provide a right for the general public to have access to the materials and the judgment of a case in criminal proceedings.61

The European Parliament considered these derogations to be very broad. It therefore preferred deleting the entire obligation altogether. The Presidency regretted this decision, since it felt that, despite the derogations, the obligation provided added value. It accepted the point of view of the European Parliament, however, with a view to reaching a compromise on the draft Directive.62

10. Presence at court hearings (Arts. 15 and 16)

Arts. 15 and 16 provide for the right of a child to be accompanied by the holder of parental responsibility during the criminal proceedings, the right to be present at the trial, and the right to a new trial.

The title of Art. 15 as initially proposed, namely "Right of access to court hearings of the holder of parental responsibility", was replaced by "Right of the child to be accompanied by the holder of parental responsibility." This makes sense, since the Directive is meant to give rights to children, not to their parents (or similar persons).

In line with Art. 5, Art. 15 provides certain derogations allowing Member States to decide that not the holder of parental responsibility, but another appropriate adult may accompany the child during court hearings.63 However, it is made clear that, when the circumstances justifying a derogation have ceased to exist, the child again has the right to be accompanied by the holder of parental responsibility during any remaining court hearings.64

The European Parliament requested adding a right for children to be accompanied by the holder of parental responsibility during stages of the proceedings other than court hearings, e.g. during questioning at the police station. The Council fiercely objected this request on the grounds that this could substantially jeopardize the criminal proceedings. In order to reach a compromise, however, the Council agreed to the insertion of the new provision on condition that, during such other stage, children may only be accompanied by the holder of parental responsibility if the competent authority considers that it is in the child’s best interests to be accompanied by that person and if the presence of that person will not prejudice the criminal proceedings. This enables the competent authorities to maintain control.

As regards the right of children to appear in person at the trial, the basic idea of the Commission’s proposal did not cause any particular problems. Upon suggestion by the European Parliament, it was agreed that children should be able to "participate effectively" in the trial, which notably should mean that they should be given the opportunity to be heard and express their views. This is a useful amelioration.

12. Other Articles (Arts. 20 and 22)

Art. 20 on training has been modelled on a corresponding provision in Directive 2012/29/EU on the protection of victims.65 Art. 22 provides that the costs resulting from the application of the provisions on the individual assessment, the medical examination,66 and the audio-visual recording should be met by the Member States, irrespective of the outcome of the proceedings.67

IV. Concluding Remarks

Procedural rights for children are already contained in various instruments of international law. These instruments, however, often have no (real) binding nature, and the enforcement instruments are weak. It is therefore very positive that Directive (EU) 2016/800 introduces minimum standards on procedural safeguards for children in Union law. The application and interpretation of these standards will now come under the control of the Commission and the Court of Justice of the European Union.

The negotiations leading to the Directive were very intense and complicated. This can i.a. be explained by the fact that, on several points, similar rights applicable to all suspects and accused persons already exist in other measures. As a result, there was a constant search to determine the available margins to do something "extra" for children.

On some points, the final text of this Directive may fall short of expectations. In respect of several important issues, however, the Directive provides added value, including:

The right to information;

The individual assessment;

Assistance by a lawyer (combined with legal aid);

The treatment of children when deprived of liberty; and

The right to participate at the trial.

During the trilogue negotiations, the Member States in the Council had diverging positions: while some felt that the standards as set out in the general approach should be maintained, others aligned with the European Parliament and the Commission, which wanted to provide higher standards of protection for children. In the end, however, all Member States voted in favour of the final compromise text of the Directive.68

O.J. L 132, 21.5.2016, p. 1; see also the news section „Procedural Safeguards”, in this issue.↩︎

O.J. C 295, 4.12.2009, p. 1.↩︎

O.J. L 280, 26.10.2010, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras and L. De Matteis, "The Directive on the right to interpretation and translation in criminal proceedings", eucrim 4/2010, p. 153.↩︎

O.J. L 142, 1.6.2012, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras, and L. De Matteis, "The Directive on the right to information", eucrim 1/2013, p. 22.↩︎

O.J. L 294, 6.11.2013, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras, "The Directive on the right of access to a lawyer in criminal proceedings and in European arrest warrant proceedings", eucrim 1/2014, p. 32.↩︎

O.J. L 65, 11.3.2016, p. 1. See, on this measure, S. Cras and Anže Erbežnik, "The Directive on the presumption of innocence and the right to be present at trial", eucrim 1/2016, p. 25.↩︎

The Commission considered whether the term "minors" should be used instead of "children". The latter term was finally employed since this is also the one used in international standards, e.g., the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) and the Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child-friendly justice (2010).↩︎

Explanatory memorandum, point 9.↩︎

COM(2011) 60 final (action 2).↩︎

O.J. C 378, 24.12.2013, p. 8.↩︎

The Netherlands issued a reasoned opinion on the basis of Protocol N°2 to the Lisbon Treaty, stating that the proposal of the Commission did not comply with the principle of subsidiarity. This was a bit curious, since this measure (at least a measure on special safeguards for vulnerable persons) was already foreseen by the Roadmap, which had been adopted unanimously by the Council.↩︎

COM (2013)821.↩︎

COM (2013)824.↩︎

Council doc. 7047/14, p. 1.↩︎

Council doc. 10065/14.↩︎

See, e.g., "Joint position paper on the proposed directive on procedural safeguards for children suspected or accused in criminal proceedings", presented by Fair Trials and the Children’s Rights Alliance for England (CRAE) in September 2014 (from point 14).↩︎

In application of Art. 294 TFEU.↩︎

The letter by the President of COREPER to the European Parliament contains the following standard text:

"Following the informal meeting between the representatives of the three institutions, the final compromise package was agreed today by the Permanent Representatives' Committee. I am therefore now in a position to confirm that, should the European Parliament adopt its position at first reading, in accordance with Article 294 paragraph 3 of the Treaty, in the form set out in the compromise package contained in the Annex to this letter (subject to revision by the legal linguists of both institutions), the Council would, in accordance with Article 294, paragraph 4 of the Treaty, approve the European Parliament’s position and the act shall be adopted in the wording which corresponds to the European Parliament’s position."↩︎

See, e.g., the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child, Art. 1.↩︎

Recital 13.↩︎

Art. 5, point (b) of Art. 8(3), and Art. 15.↩︎

Directive 2010/64/EU on the right to interpretation and translation, Art. 2(2); Directive 2012/13/EU on the right to information, Art. 2(1); and Directive 2013/48/EU on the right of access to a lawyer, Art. 2(1).↩︎

It was also observed that, after a final sentence, the persons concerned would no longer be suspects or accused persons but sentenced persons, which would not correspond with the title and subject matter of the Directive.↩︎

Art. 4 complements the obligation to provide information on rights under Arts. 3 to 7 of Directive 2012/13/EU.↩︎

ECtHR, Panovits v. Cyprus, 11 December 2008 (Appl. no. 4268/04), para. 67.↩︎

The stages of the proceedings are as follows: (1) promptly when children are made aware that they are suspected or accused; (2) at the earliest appropriate stage in the proceedings; and (3) upon deprivation of liberty.↩︎

Art. 4(2).↩︎

Recital 19.↩︎

Council Regulation (EC) 2201/2003 concerning jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in matrimonial matters and the matters of parental responsibility (O.J. L 338, 23.12.2003, p. 1), Art. 2 (7 and 8).↩︎

Art. 3(2) and (3).↩︎

While the intention of the Commission was clear, doubts were expressed as to whether the drafting of Art. 6 of the Commission proposal would effectively lead to mandatory assistance by a lawyer. The Commission had proposed the following: "Member States shall ensure that children are assisted by a lawyer throughout the criminal proceedings in accordance with Directive 2013/48/EU. The right to [read: of] access to a lawyer cannot be waived." The A2L Directive provides an opportunity for suspects or accused persons to have access to a lawyer. Not being able to waive that opportunity does not seem to result in the child being effectively assisted by a lawyer.↩︎

See S. Cras, eucrim 1/2014 op. cit., p. 36.↩︎

"In principle" because it seems fair to make an exception for the situation in which a lawyer has been arranged/appointed but the lawyer does not turn up during the proceedings. See also in this regard Art. 6(7) of the Directive as finally agreed.↩︎

Council doc. 13199/15, p. 4.↩︎

Council doc. 13901/15, p. 3.↩︎

See, e.g., Council doc. 14470/15, p. 4 and p. 5.↩︎

Art. 6(6). The criteria are clearly inspired by Strasbourg case law, see, e.g. ECtHR Quaranta v. Switzerland, 24 May 1991 (Appl. no. 12744/87), para. 32-38.↩︎

Art. 6(2).↩︎

Recital 25.↩︎

Recital 26. This recital also states that where the application of a provision of the A2L Directive would make it impossible for a child to be assisted by a lawyer under the children Directive, such provision should not apply to the right of children to have access to a lawyer under the A2L Directive. An example in this regard is the derogation for geographical remoteness as set out in Art. 3(5) of the A2L Directive.↩︎

See recital 39.↩︎

Art. 7(2).↩︎

Art. 7(4).↩︎

CoE Guidelines on child-friendly justice, op. cit., point IV.A.16.↩︎

Art. 7(7).↩︎

Joint position paper presented by Fair Trials and CRAE, op. cit., point 33.↩︎

Art. 8(4).↩︎

Explanatory memorandum, point 40.↩︎

Audio-visual recording can also have other negative effects. A representative of one Member State accounted that, under the law of his Member State, it is not only obligatory to make audio-visual recordings of questioning of children but it is also obligatory to provide the child with a copy of the recording upon request. This provokes the following situation: once in a while teenagers who often commit crimes come together to watch recordings of themselves being questioned by the police. The person who shows off as having been the "toughest" with the police during the recorded questioning is awarded a prize. Obviously, in such situations, the obligation of audio-visual recording has unwanted consequences.↩︎

For example, the CoE Guidelines on child-friendly justice, op. cit., point IV.A.19, and the UN Convention on the rights of the child, Art. 37 b).↩︎

Recital 45.↩︎

Alternative measures could e.g. be a prohibition for the child to be in certain places, restrictions concerning contact with specific persons, reporting obligations to competent authorities, participation in educational programmes, etc. See recital 46.↩︎

The measures should, where appropriate and proportionate, also apply to situations of deprivation of liberty other than detention, see Art. 12(5), last sub-paragraphs.↩︎

CoE Guidelines on child-friendly justice, op. cit., point IV.A.20.↩︎

Recital 50.↩︎

Recital 49.↩︎

See e.g. the CoE Guidelines on child-friendly justice, op. cit., point IV.A.6.↩︎

Explanatory memorandum, point 51.↩︎

General Approach (Council doc. 10065/14), recital 28.↩︎

Compare Art. 5(3) of the Directive 2013/48/EU.↩︎

Council doc. 13199/15, p. 26.↩︎

Council doc. 13901/15, p. 4.↩︎

Art. 15(2).↩︎

Art. 15(3).↩︎

Directive 2012/29/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime (O.J. L 15/57, 14.11.2012), Art. 25.↩︎

Unless covered by a medical insurance.↩︎

The request from certain Member States to allow for the recovery of such costs in case of conviction of the child (Council doc. 10065/14, Art. 21.2) was, fortunately, not accepted in the final text. It would have been contrary to the aim of enhancing the procedural safeguards for children, it could have entailed "fair justice" risks, and it would not have been in line with other instruments, in particular Directive 2010/64/EU, which equally foresees in its Art. 4 that the Member States should meet the costs.↩︎

It should be noted, however, that Italy made a declaration upon the adoption of the Directive, stating that it maintained concerns about the level of protection accorded by the Directive and that, when implementing the Directive, it would continue to be inspired by the high levels of protection its legal system already provides for children in criminal proceedings.↩︎

This article reflects solely the opinion of the author and not that of the institution for which he works. The author would like to thank Ingrid Breit for her valuable commentson the article. Any mistakes, however, should be attributed to the author only.