Beyond Freezing? The EU’s Targeted Sanctions against Russia's Political and Economic Elites, and their Implementation and Further Tightening in Germany

Abstract

Since 2014 persons allegedly involved in or supporting the undermining or threatening of the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine are subject to freezing measures against their property and other financial resources within the European Union. As part of several comprehensive political and economic sanctioning packages initiated by the Commission and the Council after the invasion of February 2022, these financial sanctions have been significantly extended, currently targeting, inter alia, some 1,200 individuals, most of them of Russian nationality. This article provides a general overview of the concept of the EU's so-called targeted ("smart") sanctions and the adaption of this instrument to Russia's warfare in Ukraine, followed by an exploration of the plans for a further tightening of such measures as proposed by the European Commission. The intention is to go beyond the – temporary – freezing of assets owned by listed individuals and entities, thus promoting their seizure and confiscation. The new extended measures introduced quite recently in Germany clearly anticipate this new policy direction. They can be seen as a blueprint and have been depicted as point of reference for a critical analysis of such symbolic legislative activism which raises serious fundamental rights concerns.

I. Introduction

"We will target the assets of Russian oligarchs." With this clear message presented by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen earlier this year, the plans of the Commission to further tighten the already existing targeted sanctions regime related to Russia's war against Ukraine were publicly communicated. In her statement, she further announced:

"The European Union is looking into ways of using the frozen assets of Russian oligarchs to fund the reconstruction of Ukraine after the war. Our lawyers are working intensively on finding possible ways of using frozen assets of the oligarchs for the rebuilding of Ukraine."1

The sheer amount of assets, which are already under freeze, provides a considerable incentive for such a policy plan. According to various estimates of May 2022, assets frozen as a result of Western sanctions may total between 300 and 500 billion US dollars;2 of these, approximately €200 billion in Belgium alone.3 A possible way forward to realizing such "use" of (private) property is the criminalisation of sanctions evasion in connection to which new grounds for confiscation may be established.4

This article is meant to provide a general introduction to the current system of EU sanctions, its origins and current practices as well as to give some guidance through the jungle of relevant EU documents. Given that Germany is one of the first EU Member States which already implemented such additional penal measures, without waiting for EU framework legislation, and based on a portrayal of Germany's actual amendments, the article also discusses potential infringements of fundamental rights arising from such a tightened concept.

II. EU's Targeted Sanctions Regime

1. General Concept

The so-called targeted sanctions5 are a genuine instrument of the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) that can be imposed under Chapter 2 of the Treaty of the European Union (TEU). Art. 29 TEU provides an explicit legal basis for Council decisions imposing such sanctions. The procedure is regulated in Art. 215 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU); its second paragraph authorises the Union to impose sanctions against natural or legal persons, groups, and non-state entities.6 Their formal name is "restrictive measures".7

The first legal document imposing restrictive measures was adopted on 28 October 1996 and concerned the imposition of sanctions on Burma/Myanmar. The measures imposed at that occasion were still rather modest: a visa ban for selected politicians and military officers, and a suspension of high-level bilateral governmental visits.8 Since then, the concept developed to become one of the most dynamic and impactful instruments of the EU's foreign policy.9 Meanwhile, targeted sanctions are being imposed at many occasions. Over time a change in the use of restrictive measures has been identified, which has shifted from targeting states to targeting individuals and non-state entities.10 Parallel to the EU's autonomous sanctions, UN-determined sanctions have been adopted and implemented by the European Union as well.11 The related measures are self-executing; transformation into domestic law is not required.

The purpose and scope of targeted sanctions can be diverse, aiming to promote peace and security, to prevent conflicts, to support democracy, and to defend the principles of international law. They can be imposed in a variety of different forms, and selected and combined according to a modular concept.12 Standard sanctions mainly include economic boycotts, restrictions on services, travel restrictions (including visa or travel bans), flight bans, arms embargoes and embargoes for dual use goods, restrictions on equipment used for internal repression and other specific imports or exports, and most importantly, financial restrictions. In addition, atypical measures customised to specific situations are also possible. For the purpose of this article, the focus is on the financial restrictions.

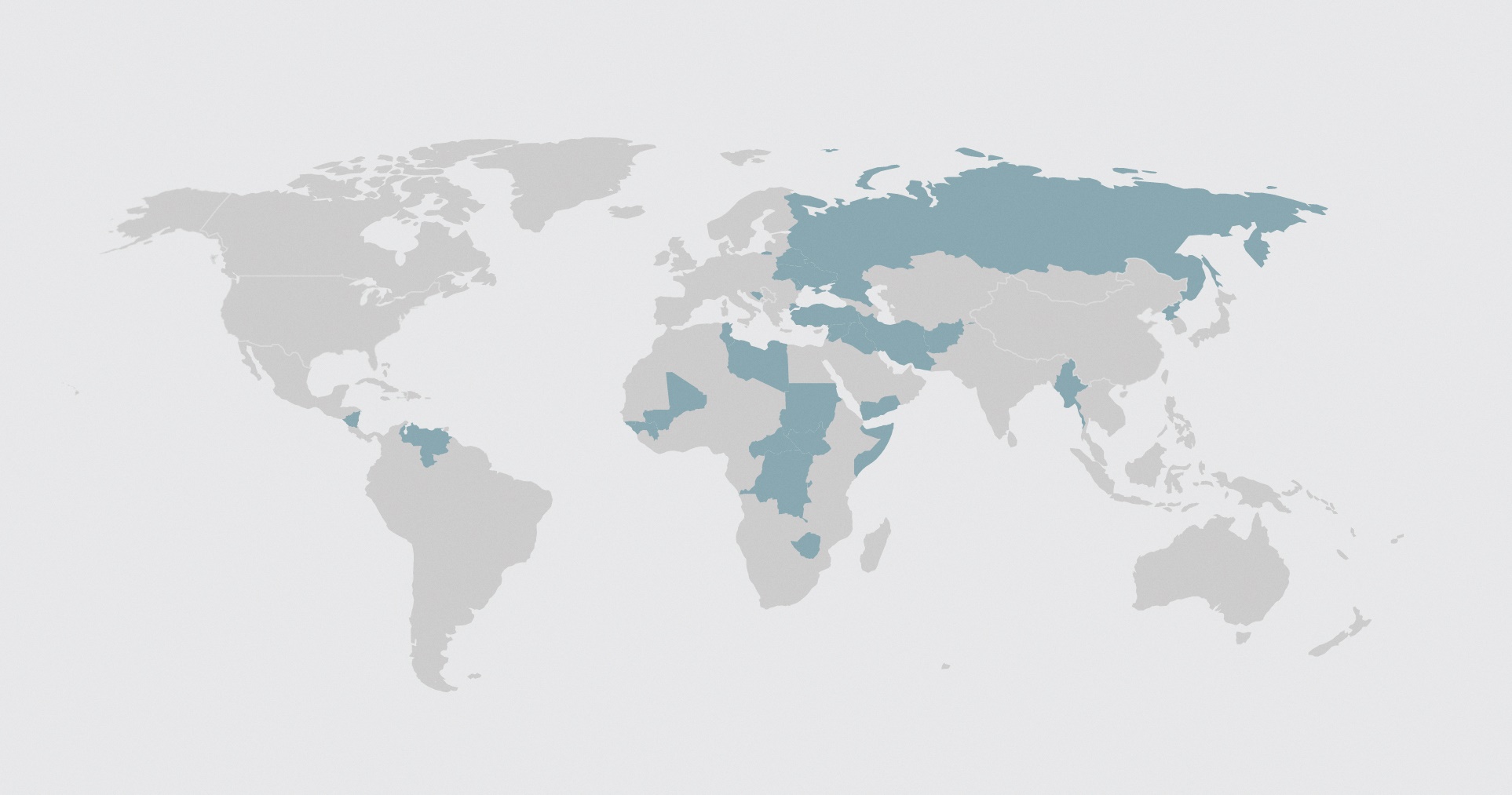

Distinct from the current public perception, the sanctions regime is not an instrument that would mainly or even exclusively target Russia. As can be seen from the map provided in Figure 1, targeted sanctions are currently in force in relation to a considerable number of states, members of their governments or illegitimate regimes, and individuals or entities supporting those or fighting against those, respectively. Besides Russia, the EU currently targets, inter alia, the following countries: Belarus, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Sudan and South Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Venezuela, Yemen, Zimbabwe, and some more.13 North America and Canada, together with Australasia and Japan are the only world regions that are totally devoid of any EU sanctions. Within Europe, the political situation in Bosnia and Hercegovina is considered to be quite unstable; accordingly, the legal basis for a potential imposition of targeted sanctions against those undertaking activities aiming to undermine the sovereignty, territorial integrity, constitutional order and international personality of Bosnia and Herzegovina, or seriously threaten the security situation there, or undermine the Dayton peace agreement, has already been passed on a preparatory status quite some years ago.14 Although EU policy against Russia has become more and more rigorous, the related sanctions have not reached yet the top position; while 39 restrictive measures have so far been put in place in the context of the Russian aggression against Ukraine, some 52 types are currently effective against North Korea; and some 24 measures have been introduced in relation to the warfare in Syria.15

Figure 1: Map of Targeted EU Sanctions in Force

Source: EU Sanctions Map (provided online at https://sanctionsmap.eu/#/main)

2. Asset Freezing

With the exception of no more than a handful of cases, asset freeze and other finance-related sanctions commonly apply in all cases. The most prominent example from the past are certainly the financial sanctions imposed in relation to the Taliban.16 This instrument is one of the most frequently amended legal acts in the area of the targeted sanctions. What had been initiated in the year 2000 as a sanctioning regime against the (first) Taliban regime of Afghanistan17 was widened in the aftermath of 9/11 into an instrument targeting "certain persons and entities associated with Usama bin Laden, the Al-Qaida network and the Taliban”. Notwithstanding its character as an UN-determined measure,18 the related Council Regulation 881/2002,19 together with its currently more than 330 amendments,20 through which the lists21 of targeted persons, groups and entities have been updated on a regular basis, developed to become the prototype of what is commonly discussed as "terror lists". This scheme raises a number of concerns related to the limited possibilities for effective judicial supervision.22 Meanwhile the title of the core Regulation (no. 881/2002) was changed again, thus widening the scope to the so-called 'Islamic State'.23

The key substance of asset freeze is stipulated in Art. 2 of that Regulation which provides:

1. All funds and economic resources belonging to, or owned or held by, a natural or legal person, group or entity designated by the Sanctions Committee and listed in [the annex hereto] shall be frozen;

2. No funds shall be made available, directly or indirectly, to, or for the benefit of, a natural or legal person, group or entity designated by the Sanctions Committee and listed in [the annex hereto];

3. No economic resources shall be made available, directly or indirectly, to, or for the benefit of, a natural or legal person, group or entity designated by the Sanctions Committee and listed in [the annex hereto], so as to enable that person, group or entity to obtain funds, goods or services.

The same wording can be found in many other legal acts as well. Meanwhile, standard formulations have been developed which are provided in the related guidelines. These include, inter alia, also the following key definitions which are regularly incorporated in the individual legal acts:24

"Freezing of funds" means preventing any move, transfer, alteration, use of, access to, or dealing with funds in any way that would result in any change in their volume, amount, location, ownership, possession, character, destination or other change that would enable the use of the funds, including portfolio management;

"Funds" means financial assets and benefits of every kind, including but not limited to:

(a) cash, cheques, claims on money, drafts, money orders and other payment instruments;

(b) deposits with financial institutions or other entities, balances on accounts, debts and debt obligations;

(c) publicly- and privately-traded securities and debt instruments, including stocks and shares, certificates representing securities, bonds, notes, warrants, debentures and derivatives contracts;

(d) interest, dividends or other income on or value accruing from or generated by assets;

(e) credit, right of set-off, guarantees, performance bonds or other financial commitments;

(f) letters of credit, bills of lading, bills of sale;

(g) documents evidencing an interest in funds or financial resources;

"Freezing of economic resources" means preventing their use to obtain funds, goods or services in any way, including, but not limited to, by selling, hiring or mortgaging them;

"Economic resources" means assets of every kind, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable, which are not funds but can be used to obtain funds, goods or services.

A further core element of the financial sanctions are the annexes related to the regulations, in which the targeted individuals and entities for which the measures will apply, are listed. Over the years, hundreds of natural and legal persons have been listed and, sometimes, de-listed again in the context of such regulations. Besides the individual impact for those affected, the selection process and final decision about the listing is a core component of the political dimension of this instrument. The measures taken should target those identified to be responsible for the policies or actions that have prompted the EU's decision to impose restrictive measures and those benefiting from and supporting such policies and actions.25 Their selection and imposition is meant to bring about the intended change in policy or activity by the target country, part of country, government, entities or individuals, in line with the objectives set out in the CFSP Council Decisions.26 Accordingly, the list has been characterised in the literature as a technology of governance.27

This political dimension has immediate implications when it comes to the determination of the legal character of the targeted sanctions in general and the freezing of assets and other financial resources in particular. As a CFSP instrument they are meant to be a political sanction in form of a temporary and partial restriction of the exercise of certain property rights; however, ownership remains with the sanctioned persons; and the restrictions will automatically lapse when the sanction regime comes to an end. In the guiding documents, the freezing has been classified as an administrative measure that is to be distinguished from judicial freezing, seizure and confiscation.28 The latter cannot be imposed within the scope of restrictive measures; the same is true in regard to any further penal intervention. Where appropriate, the related documents, such as, e.g., the Lebanon Regulation, explicitly point out that the measures have been imposed without prejudice to the ultimate judicial determination of the guilt or innocence of any individual.29 However, further penal measures, such as confiscation due to criminalisation of the breach of sanctions, might be allowed under domestic law.30

3. Sanctions Related to Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

In relation to Russia's military aggression against Ukraine, six sanction packages have been passed until now. A long list of sanctions, such as restrictions on travel, economic cooperation, imports and exports, and also on broadcast, have been imposed.31 Even caviar has been banned.32 Freezing of assets is an integral part of the sanctioning regime.33

Immediately after the annexation of the Ukrainian Crimea by Russia, the Council of the European Union already issued the first restrictive measures against persons in relation to acts that undermine or threaten the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine. Pursuant to Art. 2 of Regulation 269/2014,34 no funds or economic resources may be made available, directly or indirectly, to or for the benefit of the natural persons listed in Annex I hereto or to natural or legal persons, institutions or organisations associated with them. In addition, Art. 8(1) of the Regulation includes an explicit duty for those concerned to provide the necessary information about sanction-relevant property to the competent authority of the Member State where they are resident or located, and to the Commission. Since the beginning of the current war on the 24 February 2022, the related instruments were repeatedly extended and the list of targeted individuals and entities amended. Currently, some 1,200 individuals and almost 100 entities in Russia are sanctioned.35 Targeted persons concerned include President Putin and the political and economic elites, the so-called oligarchs, and many further private individuals who are considered to be responsible for actively supporting or implementing, actions or policies which undermine or threaten the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine, as well as stability and security in Ukraine.

Distinct from earlier cases, the lists of individuals provide extensive information about the grounds in regard to which the individuals have been listed.36 Four randomly selected examples of such "statements of reasons" from that document which read like the facts of a criminal court verdict may illustrate the reasoning behind these listing decisions:

"Function: Activist, journalist, propagandist, host of a talk show named “The Antonyms” on RT, Russian state-funded TV channel." – "[Mr. X.]37 is a journalist, who hosts the "The Antonyms" talk show on RT, Russian state-funded TV channel. He has spread anti-Ukrainian propaganda. He called Ukraine a Russian land and denigrated Ukrainians as a nation. He also threatened Ukraine with Russian invasion if Ukraine was any closer to join NATO. He suggested that such action would end up in "taking away" the constitution of Ukraine and "burning it on Khreshchatyk" together. Furthermore, he suggested that Ukraine should join Russia."38

"Function: Owner of the private investment group Volga." – "[Mr. X.] is a long-time acquaintance of the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin and is broadly described as one of his confidants. He is benefiting from his links with Russian decision-makers. He is founder and shareholder of the Volga Group, an investing group with a portfolio of investments in key-sectors of the Russian economy. The Volga Group contributes significantly to the Russian economy and its development. He is also a shareholder of Bank Rossiya which is considered the personal bank of Senior Officials of the Russian Federation. Since the illegal annexation of Crimea, Bank Rossiya has opened branches across Crimea and Sevastopol, thereby consolidating their integration into the Russian Federation. Furthermore, Bank Rossiya has important stakes in the National Media Group which in turn controls television stations which actively support the Russian government’s policies of destabilisation of Ukraine."39

"Function: Oligarch close to Vladimir Putin. One of the main shareholders of the Alfa Group." – "[Mr. X.] is one of Vladimir Putin’s closest oligarchs. He is an important shareholder of the Alfa Group, which includes one of major Russian banks, Alfa Bank. He is one of approximately 50 wealthy Russian businessmen who regularly meet with Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin. He does not operate independently of the President’s demands. His friendship with Vladimir Putin goes back to the early 1990s. When he was the Minister of Foreign Economic Relations, he helped Vladimir Putin, then deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, with regard to the Sal’ye Commission investigation. He is also known to be an especially close personal friend of the Rosneft chief Igor Sechin, a key Putin ally. Vladimir Putin’s eldest daughter Maria ran a charity project, Alfa-Endo, which was funded by Alfa Bank. […]"40

"Function: Journalist of the state-owned TV Rossiya-1, leading a political talk-show “60 minutes” (together with her husband [Mr. X]) – the most popular talk-show in Russia)." – "[Ms. X.] is a journalist of the state-owned TV station Rossiya-1. Together with her husband [Mr. X], she hosts the most popular political talk-show in Russia, “60 Minutes”, where she has spread anti-Ukrainian propaganda, and promoted a positive attitude to the annexation of Crimea and the actions of separatists in Donbas. In her TV show she consistently portrayed the situation in Ukraine in a biased manner, depicting the country as an artificial state, sustained both militarily and financially by the West and thus – a Western satellite and tool in NATO’s hands. She has also diminished Ukraine’s role to “modern anti-Russia”. Moreover, she has frequently invited such guests as Mr. Eduard Basurin, the Press Secretary of the Military Command of so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” and Mr. Denis Pushilin, head of the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic”. She expelled a guest who did not comply with Russian propaganda narrative lines, such as “Russian world” ideology. Ms. [X.] appears to be conscious of her cynical role in the Russian propaganda machine, together with her husband."41

The above quotes well underline the purely political motifs under which those entered on the list of targeted individuals have been selected. The rationale of the freezing of their properties can even be specified a bit more in view of the actual situation, in distinction from the basic concept of that instrument. In regard to the – real or alleged – supporters of Russia's aggression it is meant to be an expressive42 political sanction in form of a temporary constriction of the possibility to enjoy their – often extremely luxurious – properties located in the European Union, and their fruits. As mentioned earlier, ownership remains with the sanctioned persons, and the restrictions will automatically lapse when the sanction regime comes to an end.

III. Tendencies for a Further Tightening

1. European Union

It can be presumed that the temporary character of the current freezing measures may be one of the reasons why the financial sanctions are deemed amongst EU politicians to be not sufficiently tough. With a certain focus on the oligarchs and tempted by their financial wealth which often counts in billions of Euros, the need for a further tightening of the sanctions has been repeatedly promoted, even so by Commission President von der Leyen.43 Such a logical next step would be the seizure and confiscation of the properties concerned (with the purpose of using these assets for supporting the post-war reconstruction of Ukraine's infrastructure as mentioned above).

Meanwhile, additional penal measures, which, besides criminal prosecution, explicitly include confiscation, have already been introduced in relation to infringements of several of the economic restrictions.44 By means of an additional Regulation,45 the original Regulation 883/2014 was accordingly amended. Inter alia, its Art. 8(1) has been replaced by the following provision:

(1.) Member States shall lay down the rules on penalties, including as appropriate criminal penalties, applicable to infringements of the provisions of this Regulation and shall take all measures necessary to ensure that they are implemented. The penalties provided for must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive. Member States shall also provide for appropriate measures of confiscation of the proceeds of such infringements.

Currently, this tightening is limited to the economic sanctions provided in Regulation 883/2014; therefore, it does not apply in relation to the freezing measures under Regulation 269/2014. Nevertheless, it is referred to as a reference measure in the policy discussions in Brussels and the Member States. The Commission foresees in its proposal for a next, revised and amended (general) directive on asset recovery and confiscation46 that the entire penal asset recovery and confiscation regimes of the Member States would also apply in cases of the violation of EU's restrictive measures as a whole.47

2. Germany

Meanwhile, the German legislature has already adopted Ms. von der Leyen's idea and became a forerunner in the further tightening of the EU's sanctioning regime. In May 2022, new domestic legislation was passed, which aims to reach a more effective implementation of the EU's restrictive measures. The government bill for a so-called Sanctions Enforcement Act was introduced in the legislative process on 10 May 2022,48 followed by an extraordinarily hasty enactment: the related Act already entered into force two weeks later, i.e., on 24 May 2022, one day after its publication in the Federal Law Gazette.49/50 This piece of legislation relates to the EU sanctions regimes in general, not only to the current ones targeting the Russian aggression in Ukraine. Formally speaking, it is a technical, so-called article act,51 through which a couple of specified material laws have been amended. These include, first of all, the Foreign Trade and Payments Act, as well as the Money Laundering Act, the Banking Act, the Securities Trading Act, and the Financial Services Supervision Act.

What might on the face of it look like a bunch of technical provisions meant to clarify the administration of finance-related regulations, includes some specific provisions that, directly and indirectly, pave the way to the field of criminal law and penal intervention. Most relevant in our particular context are the amendments to the Foreign Trade and Payments Act (Außenwirtschaftsgesetz – AWG, hereinafter: FTPA).

The directive-based obligation for those listed to provide the necessary information52 was transposed into a penalised duty to declare any relevant properties concerned to the German Bundesbank or the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control without delay.53 Failure to do so is a criminal offence which may incur imprisonment of up to one year or a fine.54 The declaration has to specify all relevant details as to, e.g., value and ownership, and must be submitted in German.55 Selected third parties who have business contacts to listed persons have to file a similar report in case that they have knowledge about potentially sanction-related assets.56 The need for such a penalisation was justified by a presumption according to which unwillingness to cooperate with the authorities might be an indicator of the intention to frustrate the sanctioning regime.57 While the government bill puts explicit emphasis on the need to strictly and severely punish such manifestation of criminal behaviour,58 it fails to mention the further impact of this actual criminalisation. Not any reference – not even in a footnote – has been made to the fact that all statutory offences prescribed in Section 18 of the FTPA, are reference crimes that allow non-conviction-based confiscation. This patrimonial variant of penal confiscation59 was introduced in Germany in 2017 in transposition of the 2014 EU Directive on the freezing and confiscation of instrumentalities and proceeds of crime.60 Such an in rem procedure can be applied in cases in which a person cannot be prosecuted for legal or factual reasons, upon mere suspicion of one of the reference crimes provided.61 An initial degree of suspicion (einfacher Tatverdacht) is sufficient to order seizure of the related assets; further investigation in personam is not required, nor the prosecution or conviction of any individual.62 In principle, application of this most extensive variant of confiscation is limited to cases of particularly serious crimes, in particular those related to organised crime and terrorism. This threshold has been concretised by the (definite) catalogue of eligible reference crimes which are considered to generally justify not only the penal intervention as such but also the related presumption of illicit origin of the targeted assets.

Hence, the 2022 amendment to the FTPA automatically63 opens the door for the seizure and confiscation of such properties. However, like all variants of penal confiscation, non-conviction-based confiscation also requires, at least in principle, criminal origin or a reasonable suspicion of criminal origin of the objects or properties that shall be confiscated. Therefore, an additional – technical – step is necessary to make the undeclared properties of those listed liable for confiscation. And indeed, the FTPA further provides that any objects relating to FTPA crimes are subject to confiscation.64 As a result of this sector-related widening of the scope of confiscation, the character of the undeclared property becomes irrelevant – be it of licit or illicit origin. Such a fiction of illicitness is not new at all; it also exists since long in the area of money laundering where the law likewise stipulates that any objects relating to that offence – that is, laundered moneys – may be confiscated.65 Against this background, the term "undeclared property" earns a totally new, highly problematic meaning. Not enough, as a further side effect the criminalisation of non-compliance with its duty to declare all property also paved the way to (additional) money laundering investigations.66 Furthermore, the general rules for third-party confiscation apply.67 It may appear questionable whether the mere failure to file a declaration on property – property that is not per se incriminated – can justify such serious penal consequences (see below, IV.).

With the Sanctions Enforcement Act I several further new procedural and administrative regulations were introduced, among others:

It significantly widens the investigative powers of the competent authorities with the purpose to clarify ownership of assets and other properties.68 In particular, agencies are entitled to summon and examine witnesses, seize and secure evidence, search residence homes and business premises, and examine land registers and other public registers;

In addition, the possibilities for investigating and accessing details of bank accounts and for investigating the safety deposit boxes and security deposits of sanctioned individuals and companies were extended;69

In cases of urgency, funds and other economic resources can be secured until ownership has been clarified;70 as a concrete example, the government bill makes reference to the situation of a stopover of a suspicious airplane at a German airport the ownership of which is momentarily unclear;71

Moreover, the competences for the exchange of relevant information between agencies were expanded.72 This also applies to personal data, in compliance with data protection regulations. Data from the transparency register in which the beneficial owners are listed can also be retrieved;

Last, but not least, the responsibilities of the various agencies were clarified in more detail. Actors involved in the enforcement of the sanctions include the German Bundesbank, the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin), the Central Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), the Customs Investigations Office (ZKA), and the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA). Two of these agencies, namely, the FIU and the ZKA, are genuine law enforcement agencies whose general tasks are penal investigation into, and prosecution of, crime.

These domestic regulations go far beyond the purpose and scope of the EU's restrictive measures, at least in their current shape. They also exceed what the title of the Sanctions Enforcement Act implies, at least literally. As has been analysed here, it is not only about enforcing what is prescribed by the related EU regulations as freezing – a measure that explicitly does not include confiscation of assets frozen.

The potential power of the new, tightened national regulations already materialised in a first criminal case opened just a few weeks after their entry into force when German authorities in Bavaria, based on joint investigations,73 seized three properties (private apartments) located in Munich and a bank account, on which the monthly rent payments totalling around 3,500 Euros were received, upon suspicion of criminal offences pursuant to Section 18 of the FTPA in conjunction with Art. 2 of EU Regulation 269/2014.74

According to the facts summarised in the press release, accused persons in the Munich case are a member of the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, together with his wife who has a registered residence in Munich. They are joint owners of two apartments in Munich and generate income from the rental of their apartments. While the Duma member himself is listed in one of the annexes to EU Regulation 269/2014, the wife is targeted as a person associated with her listed husband.

As further emphasised in the press release, the public prosecutor's office was supported during their investigations by other agencies, in particular by the "Ukraine investigation group" which has been set up within the Investigation Unit for Serious and Organised Crime75 (sic!) at the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA). In particular, the BKA's expertise in the area of complex money laundering investigations has been praised as a useful resource for tracking assets targeted by the sanctions.

The penal variant of seizure was applied by the Munich prosecution authorities notwithstanding the fact that an administrative seizure procedure would be available as well. However, such an administrative seizure pursuant to Sections 9a and 9b of the FTPA is an interim measure which is of preventive nature;76 it would not allow confiscation of the related assets.

IV. Discussion

In its sanctions guidelines the Council of the European Union clearly emphasised that the listing of targeted persons and entities must respect fundamental rights.77 However, the amendment of the current system of asset freezing with an additional penal component in fact raises such fundamental rights concerns which go far beyond a formal critique of an unreasonable blurring of political and penal instruments. The headline of one of the recent press releases by the Commission well illustrates the basic problem; with their announcement that the

"EU proposes new rules to confiscate assets of criminals and oligarchs evading sanctions",78

criminals and oligarchs are equated. This is to some extent irritating, for not to say disconcerting. The exemplary cases shown above79 have also been selected for the purpose of this article to demonstrate that the targeted individuals are, without doubt, responsible for the dissemination of disgusting attitudes; some of these persons may be even marionettes of Putin's regime – but they can hardly be labelled criminals (at least most of them). Notwithstanding the frequently dubious appearance of the oligarchs' wealth, there is no evidence that their property might have been acquired with criminal means. This is particularly true for private persons who do not have any political function.

Confiscation is much more than a "restrictive measure". Distinct to the current freezing which is a temporary partial suspension of (most of the) property rights,80 confiscation is final and means nothing less than expropriation. The temporary character of the original measure is extinguished. The political idea of making use of the confiscated assets for the reconstruction of Ukraine after the war gives the notion of an appropriation of external private properties81 for political and moral reasons. Of course, there can be no doubt that Russia will have to take responsibility and make amends for all the damage caused by its intervention. This is, however, a matter of international litigation, and also an issue to be addressed in a future peace agreement, but not a responsibility for which private citizens have to stand for with their private property.

The example of the criminalisation as recently introduced in Germany points to some fundamental rights problems. First of all, the right to private property may be at stake. In the past, the German Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht, BVerfG) constantly held that penal confiscation does not violate the constitutional guarantee of private property.82 According to the Court's interpretation, property derived from crime does not enjoy constitutional protection from the outset. Therefore, penal confiscation is considered to be a (penal) variant of the civil condictio sine causa or ex iniusta causa action aiming to the dissolution of unjust enrichment.83 However, such a concept necessarily requires evidence, or at least strong indication, of illicit origin of the assets that are subject to confiscation. This is not the case in regard to the property of the individuals sanctioned. Next comes the principle of proportionality. Even if the criminalisation of the failure to declare the property would be considered reasonable, doubts might be raised as to whether the confiscation of property can be justified in light of the actual criminal substance of such non-compliance which could also be seen as a contravention rather than a crime.

Further doubts relate to the principles of legality and the related right to fair trial and right to effective defence. The legal fiction of German law according to which all objects relating to FTPA crimes, which now include the failure to declare all sanction-related property, are subject to confiscation84 makes a significant difference to all other scenarios of confiscation, conviction- and non-conviction-based ones. Distinct from the standard procedures on confiscation of allegedly illicit property, those concerned do not have the chance to demonstrate legal origin of their property. Because in regard to the legal fiction that automatically applies in FTPA cases, rebuttal is neither foreseen nor procedurally relevant. The fact alone that property has not been declared is meant to justify the rigid consequence of confiscation. This situation is likely to induce some parallels to the civil forfeiture regime applied in the US.85 In light of the wide range of circumstances which allow confiscation of property without evidence on criminal conduct, Levy86 once spoke of that system as a "license to steal".

The penal duty to declare private property might also be seen as an infringement of the right to privacy. What justifies backing the obligation to register private property with state agencies by introducing a statutory offence that provides a criminal penalty in case of non-compliance? Admittedly, such an obligation exists in the field of taxation, too. However, in the latter case the duty to provide the necessary information has been introduced for the purpose of fair and proper calculation of taxes. The information to be delivered in that context enjoys fiscal secrecy, and the procedure leaves the property rights completely untouched. The possibility to enjoy private property and the various rights connected to it include, in principle, the right to keep the related information undisclosed. In relation to the EU sanctions, though, the disclosure of the requested information enforced by penal means is to understood as – active – self-subjection to an immediate restriction of the rights of exercise of the property concerned.

Last, but not least, the criminalisation bears the possibility of imposition of further non-penal consequences that might add up to a potential conviction and confiscation. These are of particular relevance for non-nationals. Among a variety of such collateral consequences, criminal conviction can have serious impact also for immigration and visa issuance.87 Consequently, non-compliance with the obligation to register sanction-relevant property can impede the future options of those convicted to re-enter the EU and travel around, even if the current visa and travel restrictions imposed as part of the current sanction regime have lapsed.

The concerns which could be mapped out here only in short, will have to be examined in more detail by domestic and European courts. And, on a side note, many details of the non-conviction-based confiscation legislation systems have neither found final judicial approval yet.

V. Outlook

Making the Russian regime and society pay for the breach of international law, with its dramatic loss of lives and immeasurable material damages, is more than justified. However, it is questionable whether the idea to make the penal confiscation system available to contribute to such aim is an adequate legal means to pursue this aim.

Over the centuries, the purpose of, and legal rules for, confiscation have significantly changed. In her historic review, Stöckel reminds of ancient instruments of confiscation that were categorised in those times as "mort civile” (civil death).88 It is not even necessary to go back so far. In the last century, such criminal law-based measures of expropriation had been readily utilised during communism in the jurisdictions in Eastern Europe as an instrument for punishing and eliminating political opponents and dissidents in case of alleged political "crimes" against socialist economy or socialist society or ideology.89 The penal code of some of those states, namely, East Germany (the former German Democratic Republic), even provided for an extra clause on non-conviction based confiscation90 which in regard to both, its concept and wording, shows perplexing similarities to the related provision in its modern shape.91 In essence, such kind of policy-driven confiscation is a totalitarian concept that should never be re-introduced.

Imagine Russia or China or any other totalitarian regime would impose similar measures against, e.g., the US's economic elites, confiscating properties owned by Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffet, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and others. There can be no doubt that the outrage in the democratic parts of the would be tremendous – and rightly so.

After all, for the sake of the credibility of the European principles of the liberal and rule-of-law based model of society, any impression of an instrumentalisation of criminal law for the purpose of political or moral justness should be avoided. Otherwise the integrity of both, the criminal justice systems of the Member States and the political sanctioning regimes of the European Union, would be at risk.

Statements by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen; quoted after Reuters, <www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-exploring-using-oligarchs-frozen-assets-rebuild-ukraine-von-der-leyen-2022-05-19/>. All hyperlinks in this article were last accessed on 8 August 2022.↩︎

See <www.ukrinform.net/rubric-polytics/3523199-ec-preparing-legal-framework-for-confiscation-of-russian-assets-in-favor-of-ukraine-von-der-leyen.html>.↩︎

Wirtschaftswoche of 21. April 2022, <www.wiwo.de/my/politik/europa/russland-sanktionen-dieser-mann-hat-mehr-als-200-russische-milliarden-eingefroren/28268864.html?ticket=ST-94093-kJncytihMIjDC9KbcrSC-cas01.example.org>.↩︎

See, e.g., <www.politico.eu/article/eu-moves-to-confiscate-russian-oligarchs-assets/>.↩︎

Alternatively, they are also referred to as "smart sanctions"; for more details on the terminology, see E.V. Stöckel, Smart Sanctions in the European Union, 2014, p. 29.↩︎

Art. 215(3) TFEU further provides that such measures shall include necessary provisions on legal safeguards.↩︎

Council of the European Union, Sanctions Guidelines – update, 4 May 2018, document no. 5664/18, <https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-5664-2018-INIT/en/pdf> ( hereinafter: EU Guidelines).↩︎

Common Position 96/635/CFSP of 28 October 1996 on Burma/Myanmar, O.J., L 287, 8.11.1996, 1.↩︎

S. Sattler, “Einführung in das Sanktionsrecht”, (2019) Juristische Schulung (JuS), 18.↩︎

F. Giumelli, “Sanctions as a Regional Security Instrument: EU Restrictive Measures Examined”, in: E. Cusumanoand S. Hofmaier (eds.), Projecting Resilience Across the Mediterranean, 2020, p103119.↩︎

For a detailed overview, see Stöckel, op. cit. (n. 5), pp. 89 et seq., 142 et seq.↩︎

Sattler, op. cit. (n. 9), 19.↩︎

For a full list, see <https://sanctionsmap.eu/#/main>.↩︎

Council Decision 2011/173/CFSP of 21 March 2011 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, O.J. L 76, 22 March 2011, 68.↩︎

All details relate to the situation on 1 August 2022.↩︎

For an in-depth analysis, see R. Tehrani, Die "Smart Sanctions" im Kampf gegen den Terrorismus, 2014.↩︎

Council Regulation (EC) 337/2000 of 14 February 2000 concerning a flight ban and a freeze of funds and other financial resources in respect of the Taliban of Afghanistan, O.J. L 43, 16 February 2000, 1.↩︎

UN-determined means that the listing and de-listing is mainly prepared by the UN Sanctions Committee in New York. From a conceptual point of view, instruments such as Regulation 881/2002 are fully comparable with the EU's autonomous instruments. The EU's autonomous (additional) anti-terrorism instruments have their origin in Council Regulation 580/2001 of 27 December 2001 on specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities with a view to combating terrorism, O.J. L 344, 28 December 2001, 70.↩︎

Council Regulation (EC) 881/2002 of 27 May 2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with Usama bin Laden, the Al-Qaida network and the Taliban, and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 467/2001 prohibiting the export of certain goods and services to Afghanistan, strengthening the flight ban and extending the freeze of funds and other financial resources in respect of the Taliban of Afghanistan, O.J. L 139, 29 May 2002, 9.↩︎

See, most recently, Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/413 of 10 March 2022 amending for the 330th time Council Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with the ISIL (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida organisations, O.J. L 85, 14 March 2022, 1.↩︎

Provided in annexes I and II hereto.↩︎

The issues arising cannot be discused in the context of this chapter. For more details, see, e.g., N. Zelyova, “Restrictive measures – sanctions compliance, implementation and judicial review challenges in the common foreign and security policy of the European Union”, (2021) ERA Forum , 159. See also the Study commisssioned by the European Parliament, Subcommittee of Human Rights, on targeted sanctions against individuals on grounds of human rights violations – impact, trends and prosepects on EU level, April 2018, <www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EXPO_STU(2018)603869>.↩︎

Council Regulation (EU) 2016/363 of 14 March 2016 amending Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with the Al-Qaida network, O.J. L. 68, 15 March 2016, 1, through which the former title of the core act was replaced by the new title "Council Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 of 27 May 2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with the ISIL (Da'esh) and Al-Qaida organisations".↩︎

See EU Guidelines, op. cit. (n. 7), paras. 59 to 61.↩︎

See EU Guidelines, op. cit. (n. 7), para. 13, which further explains that the individualised imposition of the targeted measures is considered to be more effective than indiscriminate measures as they help to minimise adverse consequences for those not responsible for such policies and actions.↩︎

See EU Guidelines, op. cit. (n. 7), para. 4.↩︎

G. Sullivan, The Law of the List, 2020, pp. 59 et seq.↩︎

Council of the European Union, Update of the EU Best Practices for the effective implementation of restrictive measures, 4 May 2018, document no. 8519/18, para. 28, <https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-8519-2018-INIT/en/pdf> (herinafter: EU Best Practices).↩︎

Council Regulation (EC) 305/2006 of 21 February 2006 imposing specific restrictive measures against certain persons suspected of involvement in the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, O.J. L 51, 22 February 2006, 1, recital 2.↩︎

EU Best Practices, op. cit. (n. 28) paras. 29 and 48.↩︎

For a comprehensive overview of the current EU sanction regimes, see <https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/international-relations/restrictive-measures-sanctions/overview-sanctions-and-related-tools_en>.↩︎

See Annex XXI to Regulation (EU) 833/2014.↩︎

For a consolidated list of financial sanctions, see <https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/consolidated-list-of-persons-groups-and-entities-subject-to-eu-financial-sanctions?locale=en>.↩︎

Council Regulation (EU) 269/2014 of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine, O.J. L 78, 17 March 2014, 6.↩︎

Press release of 16 July 2022 by Josep Borrell, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, <https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/sanctions-against-russia-are-working_en>.↩︎

See, e.g., Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/336 of 28 February 2022 implementing Regulation (EU) No 269/2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine, O.J. L 58, 28 February 2022, 1.↩︎

All real names of listed persons provided in the original document have been anonymized for the purpose of this article. All of them were listed as of 28 February 2022.↩︎

Listed under no. 688.↩︎

Listed under no. 694.↩︎

Listed under no. 674.↩︎

Listed under no. 683.↩︎

Expressiveness means that through its publication the measure also carries a clear political message.↩︎

See introduction, n. 1.↩︎

See Regulation (EU) 833/2014 of 31 July 2014 concerning restrictive measures in view of Russia’s actions destabilising the situation in Ukraine, O.J. L 229, 31 July 2014, 1.↩︎

Council Regulation (EU) 2022/879 of 3 June 2022 amending Regulation (EU) 833/2014 concerning restrictive measures in view of Russia’s actions destabilising the situation in Ukraine, O.J. L 153, 3 June 2022, 53.↩︎

Proposal of 25.05.2022, COM(2022) 245 final – 2022/0167 (COD).↩︎

Art. 2 para. 3 of the draft proposal for a new directive ("scope").↩︎

See Bundestags-Drucksache 20/1740 of 10 May2022 (hereinafter: government bill).↩︎

First Act for More Effective Enforcement of EU Sanctions (Sanctions Enforcement Act I – Sanktionsdurchsetzungsgesetz I) of 23.05.2022, BGBl. I (Federal Law Gazette, part I), p. 754.↩︎

An additional Sanctions Enforcement Act II is under preparation. It shall provide the legal basis for establishing a national register for assets subject to sanctions and the setting up of a special whistleblower hotline. See <www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Pressemitteilungen/Finanzpolitik/2022/05/2022-05-10-sanktionsdurchsetzungsgesetz.html>.↩︎

Artikelgesetz.↩︎

See Art. 8 para. 1 of Council Regulation 269/2014, op. cit. (n. 34).↩︎

Section 23a para. 1 of the FTPA.↩︎

Section 18 para. 5b of the FTPA; according to its para. 6, attempt is punishable, too.↩︎

Section 23a para. 3 of the FTPA.↩︎

Section 23a para. 2 of the FTPA. Addressees are logistics service providers according to Sections 453 and 467 of the German Commercial Code (HGB).↩︎

See government bill, op. cit. (n. 48) p. 19.↩︎

See government bill, op. cit. (n. 48).↩︎

Section 76a para. 4 of the German Criminal Code .↩︎

Directive 2014/42/EU of 3 April 2014 on the freezing and confiscation of instrumentalities and proceeds of crime in the European Union, O.J. L. 127, 29 April 2014, 39.↩︎

See Section 76a para. 4 no. 1 to 8 of the German Criminal Code.↩︎

Section 111b of the German Code of Criminal Procedure. For more details on the system of penal asset confiscation in Germany, including its non-conviction-based variants, see M. Kilchling, “Country Report Germany – Extended Confiscation in Scope of the Fundamental Rights and General Principles of the European Union”, 2022, published online at Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, <https://konfiskata.web.amu.edu.pl/en/documents/>.↩︎

It is not known whether all those who voted in favour of the Sanctions Enforcement Act were aware of this consequence.↩︎

Section 20 para. 1 of the FTPA. This provision also existed already before the 2022 amendment.↩︎

Section 261 para. 10 of the German Criminal Code. For further details on the connections between money laundering control and asset confiscation, see B. Vogel, “Germany”, in: B. Vogel and J.-B. Maillart (eds.), National and International Anti-Money-Laundering Law. Developing the Architecture of Criminal Justice, Regulation and Data Protection, 2020, pp. 157-301.↩︎

With the 2017 amendment of the money laundering laws Germany realized a radical system change from the so-called catalogue to the “all crime principle”. For more details, see Vogel, op. cit. (n. 65).↩︎

Section 20 para. 2 of the FTPA in conjunction with Section 74a of the Penal Code.↩︎

Section 9a of the FTPA.↩︎

Section 24c of the Banking Act, as amended by Articel 3 of the Sanctions Enforcement Act I.↩︎

Section 9b of the FTPA.↩︎

See government bill of 10.05.2022, op. cit. (n. ##), p. 17.↩︎

Section 24 of the FTPA.↩︎

Involved were the Munich prosecutor's office, the Federal Criminal Police Office (ΒKA), the Munich Police Headquarters and the Munich Tax Office.↩︎

Public Prosecution Office Munich I, press release no. 03 of 20 June 2022, <www.justiz.bayern.de/gerichte-und-behoerden/staatsanwaltschaft/muenchen-1/presse/2022/3.php>.↩︎

Unit SO33.↩︎

See government bill, loc. cit. (n. 48), p. 17.↩︎

EU Guidelines, op. cit. (n. 7), para. 15.↩︎

Press release of 25 May 2022 by the European Commission, DG for Migration and Home Affairs, , <https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-proposes-new-rules-confiscate-assets-criminals-and-oligarchs-evading-sanctions-2022-05-25_en>.↩︎

See above, sub-chapter III.3.↩︎

Accordingly confirmed by the ECJ, 3 September 2008, Joined Cases C‑402/05 P and C‑415/05 P,Kadi and Al Barakaat, para. 358. For more details, see also Tehrani, 2014, op. cit. (n. 16), pp. 128 et seq.↩︎

Distinct from the case of private properties, the situation might be different in regard to the frozen funds of the Russian Central Bank and other public institutions.↩︎

BVerfG, ruling of 12 December1967, Official Case Reports BVerfGE 22, 387; ruling of 14. January 2004, BVerfGE 110, 1 ; and, most recently, rulings of 10. February 2021, (2021) Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW), , 1222 , and 7 April 2022, (2022) Neue Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts-, Steuer- und Unternehmensstrafrecht (NZWiSt), 276.↩︎

For more details, see Kilchling, op. cit. (n. 62).↩︎

See above, sub-chapter III.2.↩︎

For more details on the US system, see M. Tonry, “Forfeiture Laws, Practices and Controversies in the US”, (1997) European Journal on Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice (themed issue on confiscation models in a variety of jurisdictions), 294 .↩︎

L.W. Levy, A Licence to Steal: The Forfeiture of Property, 1996.↩︎

For more details, see E. Fitrakis, (ed.), Invisible Punishments. European Dimension – Greek Perspective, 2018. A comparative study on restrictions and disenfranchisement of civil and political rights after conviction in Europe is currently conducted at the Freiburg Max Planck Institute for the Study of Crime, Security and Law; see <https://csl.mpg.de/en/projects/comparative-european-study-on-restrictions-and-disenfranchisement>; the findings will be published in 2023.↩︎

Stöckel, op. cit. (n. 5), pp. 46 et seq.↩︎

See, e.g., Section 57 of the Penal Code of the former German Democratic Republic; Section 120 of the Penal Code of the former Czechoslovakia, or Articles 46 and 47 of Poland's old (socialist) Penal Code.↩︎

Section 57 para. 4 of the Penal Code of the former German Democratic Republic.↩︎

Section 76a of the German Criminal Code ; see above, III.2.↩︎

https://doi.org/10.30709/eucrim-2022-010

//

https://doi.org/10.30709/eucrim-2022-010

//